Uncategorized

How briefcase contractors plundered primary healthcare projects billions, and pushed for more

Published

6 years agoon

By

Olu Emmanuel

Letterheads, bank accounts, fixers, and damn cold hearts—all you need to bag NPHCDA’s multi-million naira contracts over and again

By Olusegun Elijah

Lonestar Procurement Services Ltd bid and won a federal government contract in 2012. Beyond its ID, the contractor has nothing else to prove it’s a corporate citizen of Nigeria: its name, promoters and their shareholding are unknown to the Corporate Affairs Commission; its office address, competence, and experience in the specialised construction industry it plays were blanked out. No tax clearance certificate, no financial position statement either. Or worse still, if it ever supplied any of these, the information was faked, and the documents presented during bidding, forged.

That is the game black-hat bidders play to win government contracts in Nigeria. And Lonestar is a grand master. It’s a limited liability company that is never registered. Yet its client—the National Primary Health Care Development Agency, along with the government contract regulator, the Bureau of Public Procurement—blinked over this. They awarded Lonestar a construction contract at a cost of N21.7 million.

And, a phantom that it is, the contractor left no footprint on his project site at Eyin Osun. Here is a rural backwater of more than 48 communities northeast of Ijebu Igbo, Ogun. “Those are the villages we could count—that we know,” Chief Makaleta, one of the baales in the area, told the National Daily. He had no idea of the population of the community. But he had the feeling that thousands of men, women, and children living all over the place would have appreciated it if the contractor had got a heart, and built the primary health centre for them—to replace the fleabag they have always called a health centre over the years.

The vacant green lot, marked for the construction at Dogo five years ago, when the contractor first came, now constantly reminds Eyin Osun of Lonestar’s wickedness. But as far as the contractor is concerned—and even the state PHCDA—the Type 1 health centre project is a done deal. A nurse, Mrs Oriyomi (not real name), was posted there in 2013 to head the ‘new’ health facility—and she has been doing just that.

At least seven other contractors, in the southwest and south-south, are in the mould of Lonestar: Ahmed Investment Ltd, 1st Project Nigeria Ltd, Okendi Nigeria Ltd, Highrise Builders, Akaba Global Logistics, La Hipperson, and Centenary Global Services Ltd. None showed up on site in Edo, Delta, and Ogun. And they all stung the federal government for N212 million (or at worst N64 million as 30 percent mobilisation fee), and ran. Nothing was done. Not even as little as ground breaking.

Down south in Delta, Best Touch Construction and Marine Services Ltd did something similar—or a little worse. It was registered, indeed, in 2010, the very year the project was first awarded. The project information on the signboard standing in decay in front of the uncompleted building at Aven Kolowane, in Patani LGA, confirms this. A freshman bidding for a government contract is a brazen violation of certain provisions of the procurement rulebook.

The Public Procurement Act regulating federal government contract award stipulates three years of post-registration experience for a contractor before bidding for small works like this. So Best Touch, in every way, wasn’t qualified to bid, in the first instance. And records the National Daily obtained from Budeshi even listed the Aven PHC project among the 2012 lots. The data from the open contract initiative the World Bank sponsored along with the Public Private Development Centre (PPDC), Premium Times, and others, might just have confirmed something more: the project was re-awarded to Best Touch in 2012. And the contract award for the Type 1 health centre, this second time, was N22. 2 million—which was just about enough for Best Touch to knock off something up to the lintel. The building has since been overtaken by weeds. But, the villagers said, there is a photoshopped version of a tastefully completed health centre the contractor already submitted to the NPHCDA.

The Con-men

Lonestar and Best Touch are two of the 141 contractors that handled over 147 projects lying in varying degree of abandonment—run-down, non-existing, or uncompleted—across the south-south and southwest.

The projects, nationwide, were those of the PHC-Under-One-Roof (PHCUOR) initiative former President Goodluck Jonathan teed-off in 2011. The policy sought to revamp the primary healthcare system for better service delivery and administration in the six geo-political zones across the nation. By some arrangement, it was embedded in the National Assembly constituency project, too—to be sponsored by the House of Reps members. The contract duration was supposed to be eight weeks. And the client was the NPHCDA founded in 1992—in the glory days of Nigeria’s primary healthcare system.

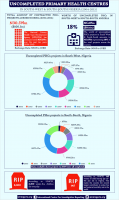

The PHCUOR was roughly the 25th reform Nigeria would attempt after the Alma-Ata Declaration on primary health care in Kazakhstan 39 years ago. It was the 11th since 1986, as WHO recorded. Unfortunately, the latest reform ended up a white elephant project. By 2015, the NPHCDA contractors had left over 400 PHCs uncompleted across the nation. The federal government said it plunked down N8.9 billion for the projects, according to a PPDC bulletin following the PHC money between 2012 and 2014. In the southwest alone, the uncompleted projects amount to over N1.2 billion while the south-south sum stands at N1.9 billion.

Uncompleted Projects for South-West and South-South

No fewer than 57—about 38 percent—of these contractors are ineligible. Twenty-six of them are unregistered mom-and-pops while 31 others registered about the time of the award—just for the project. A good number of those registered have no offices. The promoters probably operate in their pyjamas—from their bedrooms. Company profile searches the newspaper ran through the CAC database, on five of the registered contractors, returned no result. So with little or no identity, these contractors have no brand name to protect. Some of them, perhaps, took off, and ditched the contracts immediately their mobilization fees and other funds hit their bank accounts.

The unregistered contractors alone, in both regions, creamed off N542.7 million for the PHC projects abandoned, uncompleted, and not started at all. The larger chunk of it, N298.7 million, was racked up in the southwest. Those hurriedly registered for the contracts in both regions got N332 million in all. As much as N270.0 million of this largess went to the rookies, 12 of them, that mushroomed between 2012 and 2014 in the south-south alone.

That these categories of bidders ever got the contracts, in the first instance, ran afoul of the BPP Standard Bidding Document for procurement of works, a corpus of rules and regulations derived from the PPA.

The Process

Section 1, subsection C, for evaluation and qualification criteria, requires a couple of things to ensure experience and capabilities—financial, personnel and technical. All these are further expounded by the Special Instruction to Tenderers in section 2, subsection C of the same document. There the bidder is expected to have been in business (gathering experience in similar works) for three years, with at least a project to boast about. It must have an average annual turnover, too, which should be the product of the monthly cashflow from the proposed project over a year, all multiplied by 1. For Best Touch, the annual cashflow should be N132 million, same as its annual turnover. That, by all standards, was a king’s ransom for a briefcase company like this. Lonestar, which couldn’t afford a name registration, was, by that reckoning, expected to have N132 million, too, as its annual turnover. The rule also states that a contractor should have a minimum liquid asset equal to the product of the monthly inflow from the project, from its start to the certification time.

But 57 of the bidders that participated in the open bidding process between 2012 and 2014 somehow wormed their ways out of this BPP/PPA statutory mesh. And, anyhow, they clinched the contracts.

How they pulled that off is anybody’s guess.

What’s, however, obvious is one of two things: these ghost contractors and the Johnnies-come-lately palmed off fake information to the NPHCDA and the BPP during the bidding process; and the two also let things slide. Or the contractors passed on no information at all.

Either way, the PPA Special Instruction to Tenderers calls these fraudulent practices—“which mean a misrepresentation or omission of facts in order to influence a procurement process”. In that case, the client and the regulator couldn’t have claimed ignorance. And that, the procurement law says, is a corrupt practice.

In the PPA lingo, corruption means a mouthful: “offering, giving receiving, or promising to give, directly or indirectly, to any officer or employee of a procuring entity or other governmental or private authority, in any form, an employment, or any other thing of service or value, as an inducement with respect to an act or a decision of, or a method followed by, a procuring entity in connection with the procurement proceeding.” That’s stated in the SBD, Section 3, General Condition of Contract.

The NPHCDA and the BPP failed to press this then. The bureau, set up in 2007, and backed by the PPA, is expected to live up to the mark: helping the federal government get a bounce for every ounce it spends on public contracts and sales of national assets.

Granted, the bureau largely gets involved in big-ticket single contracts worth N100 million upwards, issuing certificates of no objection, among other roles. It still has powers to sanction any infraction in government procurement at any threshold, directly or indirectly—by bringing in the ICPC and EFCC. For small works like the PHC contracts whose range of value is less than N100 million, the NPHCDA’s tenders board has the approval threshold. Still the bureau also has the responsibility to review how transparent the process is.

So contract thresholds—value sizes—were no excuses for the procurement failure that marred the NPHCUOR. The problem identified, so far, is collusion. And it was far-reaching. The Senate had to wade in May. It mandated its committee on Public Procurement to investigate allegations that officials of the BPP enrich themselves, and abuse the agency’s powers to issue the certificates as they like.

A broad-brushed approach like this—for tackling corruption—is never wanting in Nigeria. It has only been leaving out a critical leg of the tripod: the contractors. And those of them leeching on the procurement system all these years have always got away with it. That happens because they easily go dark after bidding for and winning contracts. The clients and regulator help them make it darker still. That was why the House, too, asked its committee on Public Procurement and Anti-Corruption to investigate the BPP—for failing to exercise its powers on public procurement process.

A cardinal part of government procurement is making the bidding and bidders as open as possible. But the failure in this regard is obvious. Apart from names, dead web links and dumb phone lines, little else is known about the contractors, and their relationship with the procuring NPHCDA and the BPP. The layers of secrecy around them are rock-thick.

Even procurement activists and budget zealots in Nigeria haven’t been able to do much tracing the relationship tree, and following the paper trails to the companies. Or these activists, who are supposed to form a cloud of witness over government procurement, believe taking all the trouble to dig that far is not just their cup of tea. No response to questions the newspaper mailed to the Nigerian Society of Engineers. The NSE is a member of the Nigeria Contract Monitoring Coalition, and professional body the contractors are supposed to belong, as part of their eligibility requirements.

The newspaper also sent questions and an FOI request to the bureau and the NPHCDA in September, seeking details on how the 57 ineligible bidders qualified for the PHC contracts they abandoned. Neither of them responded as at the time of writing the report. No surprise, though. According to the PPDC rating of openness to Freedom of Information requests in Nigeria, the bureau ranked 86th of the 131 institutions surveyed in 2016. Its proactive disclosure (readiness to disclose) was partial, and its level of disclosure, nil.

The Threesome

But, no matter how much the BPP, its contractors, and the NPHCDA clam up, there are tell-tale signs confirming they have a way of scratching one another’s back.

The bureau’s former director-general, Emeka M. Ezeh, once alleged the existence of this sweetheart relationship amongst the three. He cited instances where sleazeballs in the procuring agency and BPP change contract categories in writing only. “‘Goods’ are deliberately classified as ‘works’,” he said in a presentation in 2015. The bottom line is to inflate the contract sums in favour of the bidders. And, after a while, everybody is happy.

It is also clear that in this relationship, beefing seldom happens. Section 54 of the PPA allows bidders to complain when they feel the process is skewed against them. Eze said it is a measure against corruption. But between 2012 and 2014, 27 ministries under the Jonathan administration had 556 petitions against them—by contractors and third parties. The ministry of health, which includes the NPHCDA, among other departments and agencies, had 39 (7.0 percent) of these, according to a comparative analysis of complaints Ezeh did.

Nigeria had 662 agencies and departments under no fewer than 30 ministries then. But the vastness didn’t prevent the omnipresence of this threesome. Even right under Ezeh’s nose, unfortunately, these ineligible contractors flourished in the BPP and the NPHCDA.

No fewer than 57 fakeys, unregistered as well as those registered for the projects in the southwest and south-south, were discovered when the National Daily ran a check in the CAC. But 48 of them were quickly expunged from the BPP contractor database after Eze left the bureau. The sweep, some kind of post-mortem, was the idea of the bureau’s new broom, Mamman Ahmadu. He might have spotted the breach or “corruption” immediately he took over. This clean-up could have only meant the bureau, between 2012 and 2014, swung the PHC procurement process for some—unregistered and incapable contractors—amongst the over 300 bidders.

No fewer than 57 fakeys, unregistered as well as those registered for the projects in the southwest and south-south, were discovered when the National Daily ran a check in the CAC. But 48 of them were quickly expunged from the BPP contractor database after Eze left the bureau. The sweep, some kind of post-mortem, was the idea of the bureau’s new broom, Mamman Ahmadu. He might have spotted the breach or “corruption” immediately he took over. This clean-up could have only meant the bureau, between 2012 and 2014, swung the PHC procurement process for some—unregistered and incapable contractors—amongst the over 300 bidders.

But the purge by the new DG was partial. Nine of those ineligible contractors still turned up like a bad penny on the bureau’s contractor database, on a list marked Interim Registration Report released in January. The BPP continues to play ball with these failed and procurement-law-breaking contractors.

To stretch the illicit dalliance further, these ineligible contractors kept bidding year in year out, in spite of their failures all along. The Budeshi data revealed at least 10 of them got awards twice in the intervening years, failing to deliver each time. But at least 14, including those failed contractors from 2013, who belonged to the four other zones, secured the agency’s recommendation again for the 2015 contracts.

Whatever the deal sweetener was, between the bureau and the bidders, it sure flowed to the client, too. The NPHCDA has a tenders board which, by the PPA 2007, comprises its executive director as chairman, the head of the procurement unit who doubles as secretary and technical sub-committee head, and other units heads as members. Dr Ado Jimada Gana Muhammad, a star-studded former head of the National Programme on Immunization, was the agency’s boss then. He took over from Dr Ali Pate in 2011, and was there all through the years the fraud and corruption festered in the agency’s procurement process.

Such impunity is not unexpected when authorities fail to exercise powers—for relationship’s sake. The unqualified contractors certainly bounced the fraud off the tenders board first, when they falsified and faked information about their eligibility during bidding evaluation. And it panned out good for them since the board had no problem with that. The NPHCDA awarded the contracts—though the law says bidders caught playing such pranks be disqualified and banned from future bidding. The malpractice could have been discovered before the contract award, especially at the evaluation stage, if the agency hadn’t just carried a straight face.

The basic efforts, which the PPA requires the board to make so the process will be open enough from bidding to the certification stage, were neglected. Or they were not handled transparently enough.

For instance, PPA’s Special Procurement Notice says procurement ads be placed in two national newspapers, and the Federal Tender Journals, in government gazettes, and on the procuring entity’s website. So at least the NPHCDA should have the ads archived on its website. That never happened. In fact, there was no procurement information whatsoever on the agency’s website as at the time of writing this report. Its ads for the past yearly projects are rather found all over online tender journals like Tenders in Nigeria and others.

When this slip-up happens, it’s usually for a purpose: to limit competition and create collusive bidding. This was glaring the way the contract values were niftily curated. In 2013, Cross Rivers contracts in Ansa, Bokim and Ikom in the south-south had N21.9 million each as bid value, which was exactly what Obafemi Owode and Odede, in Ogun, southwest, had same year.

When this slip-up happens, it’s usually for a purpose: to limit competition and create collusive bidding. This was glaring the way the contract values were niftily curated. In 2013, Cross Rivers contracts in Ansa, Bokim and Ikom in the south-south had N21.9 million each as bid value, which was exactly what Obafemi Owode and Odede, in Ogun, southwest, had same year.

On occasions, the ads get published—but with pegs buried here and there in the copy. According to Eze in his 2015 presentation at the Anti-Corruption Academy of Nigeria training on procurement process in tertiary institutions, government clients sometimes word the ads to favour certain bidders. He said they also give a very close time limit to ensure only few bidders can respond. But there is no way of knowing whether the NPHCDA didn’t do this sleight of hands in its procurement notices in those three years.

Shockingly, Eze also noted this as corruption: awards made without adequate budgetary provision. Lust for kickbacks usually breeds this. In that light, the ten-percenters (in the NPHCDA) who awarded the contracts, willy-nilly, got their cuts early on in the project execution, probably from the 30 percent mobilization fees, the only funds forth-coming at that stage. The contractors then kept the balance. Whatever happened thereafter didn’t matter. Since everybody got something, the contractors could safely skip out on the projects. And, true, many of the PHC projects were abandoned, as some of the contractors and their sympathisers tell their host communities, because the federal government didn’t make enough funds available.

That is the cover story sold the obi of a community in Igbanke, Edo. And he bought it. “The system itself is bad,” HRH Julius Chukwuyem Isitor, the Enogie of Ottah kingdom, told the National Daily. “We don’t seem to understand the government…. They didn’t mobilise them enough?”

It takes a lot of doing by the contactors to make the victims of their ruthlessness blame somebody else for the failed projects. Apart from their uncanny ability to play the system, these illegal contractors took advantage of political and clannish misgivings among the communities to cover up their tracks.

The victims

That rings true in Isitor’s domain, a 30-minute motorcycle ride from Agbor. The kingdom has a 2012 half-completed health centre. It could have been the only one serving the community of over 7,000 people, according to Isitor, had rampant elephant grasses not over-run it. He said he had documents stating the PHC was Type 1: it is supposed to have a staff lodge, a ward, a generator house, a gatehouse, a borehole, paved premises, and an ambulance, the only facility types 2 and 3 don’t have. But all Ottah has standing there over the years is the ward only, fenced, and fitted with fans, lights, and furniture—all of that for N33.3 million. And the community is regretting it now.

“Because a major express passes through the community, people get knocked down at night by speeding vehicles,” the obi said, as he talked about the death rate in his community. “Most of them die before we take them to the general hospital at Agbor in another state.” Their pregnant women, he added, go to traditional birth attenders, if they can’t afford the expenses of going to Delta to have their babies.

Isitor, in his very informed take, believed the government should take responsibility for the failure.

He might not be alone.

Ottah is a mix of the educated and the unlettered. Isitor himself is a Ph.D holder. His council of chiefs has some nice English-speaking people, too. He might be presenting the elite groupthink by speaking for the contractor. But the lowest of the low at Ottah have their different opinions. Many of them believe the contractor and the sponsor are one and the same. “They said Major and the contractor shared the money,” a villager told the newspaper.

The contractor is East Point Integrated Service Ltd, one of the 13 unregistered companies that got the NPHCDA contract five years ago in the south-south. And the sponsor is retired Brigadier-General Emmanuel O. Atewe. He was still serving in the Nigerian Army, as the Guard Brigade commander, when he sponsored the constituency project reserved for a federal rep. His last command was the Niger Delta Military Joint Task Force Operation Pulo Shield. Atewe lives in Agbor. With an air of a VIP, and the dread of his jackboots, he stands way above questioning by Ottah residents. Not because he’s got no integrity baggage. The retired general currently cringes under a 22-count charge of fraud at a federal high court in Lagos. The EFCC hauled him there for some N8.5 billion the anti-graft commission says he and three others in the Nigerian Maritime Administration and Safety Agency (NIMASA) mismanaged between September 2014 and May 2015. East Point is among the seven shell companies used in the NIMASA fraud.

Chairman House Committee on Public Procurement Hon Wale Oke didn’t respond to questions on the legality of a serving brass-hat dabbling in constituency project sponsorship.

At Opoji, in Esan Central, Edo, the opinions are divided too, to the benefit of C. Fitzadaniel International Nigeria Ltd. The company is among the 2012 defaulters. Plus it is never registered. Nobody in Opoji knows about its competence and integrity. But the community knows the project sponsor—Hon. Patrick Ikhariare. Lugard, a commercial motorcycle operator, was killing time with others in a gin-mill by the road leading to the project site that afternoon the National Daily got to Opoji. He said the honourable is his brother. “He and the contractor did well bringing the PHC to us. We are happy,” Lugard said. “They just need to do one or two things there.” His fellows looked somewhat pissed off hearing this, but they fought back their resentment. One of them who claimed he was a retired soldier later braced up to oppose Lugard. “They are on the run,’ he said. “Go see the building for yourself.”

The structure actually is far from completion—and far too small for a N19.8 million project. It only has a milk-colour single building, probably the ward, inside a forest of crawlers, saplings, and weeds, all fenced in. The old soldier hinted that the staff quarters, the generator house, and the borehole were not constructed. He had some authority as he talked, making his account more reliable. “I am the secretary of Opoji’s health committee. We have the document of what the structure is supposed to be. But they just did that and ran away,’ he said, still knocking Lugard’s praise-singing as others nodded in approval. “We have since been looking for the contractor.” But moments after, something jarred him into consciousness—like he had been the only big mouth not afraid of picking on the contractor and sponsor in front of a reporter. Old Soldier, then, suddenly toned down. “We can’t condemn them,” he said, when asked to describe the attitude of Fitzadaniel that abandoned such a vital project at Opoji. Villagers in bad health travelling 15 minutes to the nearest town, where there is a hospital, might not agree with him.

It is a similar story of non-completion and vanishing act across four of the five project sites investigated in Edo: at Okalo Ebelle, Ugun, Opoji, and Ottah. The fake contractors would erect one or two buildings, all fenced, painted, and overrun by weeds. The fifth, at Igarra, Akoko Edo, has no site at all.

Only at Ugun, Igueben LGA, the story is a little different. The illegality remains, though. Mukky Foundation, the handler of the project, was registered in 2013, the year the N21.9-million contract was awarded. The experience, competence, and other PPA requirements were either doctored or ignored. Its registered office at House 13, on plot 201 in Kardo Bimko Estate, Gwarinpa, Abuja, is fake. The security guard there told the National Daily the building is residential. On the project site, Mukky did its hardest to put up the ward, the staff lodge, and the generator house. No gatehouse, no borehole, no paved ground. Still the village, about 30 minutes’ ride to Ebelle, along the Agbor-Uromi road, couldn’t wait to have a health centre. The ward was quickly equipped, stocked, and staffed for use. However, the staff tired out, and stopped coming, the villagers explained. They blamed the government, though they were not sure of who was to blame.

At Aven Kolowane, in Delta, the villagers that spoke to the newspaper knew who to aim: Best Touch. They have petitioned the Millennium Development Goals office, Patani LGA chairman, project sponsor Hon. Nicholas Mutu, and others they believed could help them harry the contractor back to site. Mutu, 57, represents Patani-Bomadi, and chaired the House Committee on the Niger Delta Development Commission between 2009 and 2015.

An August 2015 petition lawyers from B.C.O. Ezeagu and Associates wrote, a copy of which the National Daily has, stated some NPHCDA supervisors came to equip the health centre already ticked off as completed. The community was surprised to hear that. “After much debate between our clients and the supervisors who found it hard to reconcile the site shown to then and the pictorial structure given to them by the contractor,” the lawyers stated, “it dawned on our clients they have been victims of a scam.”

It then turns out Aven, in its effort to bring the contractor back, has been barking up the wrong tree. In truth, there’s a ring around the project. “The sponsor (Mutu) is the owner of the company,” a member of the community told the newspaper. “We learnt he subcontracted it to our chairman, Josephine Abeki.” This is against Section 8 of the General Conditions of Contract in the PPA.

The community didn’t just conclude that way. They had a reason. “Whenever we called Mutu to remind him of the constituency project, so he can help look for the contractor, he would direct us to Josephine,’ said Orutu P. Williams, a permanent secretary. “ We’d call Josephine, and she, too, would ask us to call Mutu.”

Lady Josephine, however, told the National Daily she doesn’t know anything about Best Touch. “Mutu only directed them to me when they came. And as the council chairman, I gave them land,” she said in a phone interview. As usual, she directed the reporter to the government for more particulars of the contractor. And the community, she added, should solve their problem themselves. “I am no longer their chairman.”

The back and forth has frustrated many at Aven whose population Orutu said can be put at about seven million. Yet it can’t boast a single health facility. A boy died of cholera in the community late in July. And the permanent secretary also had a bad time when his son got a fracture, and there was nowhere to even go for first aid. Aven is about 15-minute ride to the nearest health centre in Patani, about 45-minute drive to Ugheli, and an hour to Oghara where he eventually took his child.

Aven wouldn’t have had to go through this hell to get primary healthcare service. Patani and its neighbour Bomadi have at least three PHCs between them. The one at Bomadi—no particular site found yet—has the largest contract value in the south-south: N56.7 million. But the contractor that hit the jackpot, Centenary Global Service Ltd, is a deadbeat like others. It was registered in 2014—for the project. No experience. It also fabricated some of its particulars. Its office address on the CAC database, House 127, Zone E, Apo Resettlement Estate, a low-brow housing project in Abuja, is a fib. “House 127 is where I live. No office there,” a man living in the apartment told the newspaper. “And it has never been an office.” With this shake-off, fading out after mobilisation became about the easiest Centenary could do.

Patani-Bomadi now has a chain of uncompleted, empty, and imaginary PHC projects and sites. They can only pile up the agony for Aven Kolowane and neighbouring communities.

“We have asked our youth not to fight yet over this neglect. Nobody fights government and win,” said Orutu. “But for how long can we hold back for a government who understands only the language of violence.”

Sure, many of Aven residents, especially those living close to the Patani-Ugheli expressway, are educated enough to know and speak this language. At Orere, in Warri South, however, only a handful can air their pain—stewing being the farthest they can go in the face of a raw deal they got from a contractor.

At Orere, a Warri South community you could dash round in 10 minutes, an abandoned health centre welcomes you as you climb down a rusty jetty that lifts you onto the community situated five meters above the river level. From Uluba, the Itsekiri community takes 15 minutes in a boat to reach. There are two health facilities there: one by Shell and the other by the NPHCDA. Both are abandoned.

Akaba Global Logistics secured the latter—though it wasn’t qualified to bid in the first place. The company was registered in 2013 when it bid and got the award for N29.9 million. The contract sum was meant to build a Type 1 PHC, complete with a small boat on the river.

But Akaba showed up only to put up just the clinic, roofed, with no doors. Other structures, including the staff quarters, gate post, generator house, and water tank, were left out. Orere’ s home chairman told the National Daily the community made a move to ensure the project was completed. ” But the contractor ran away,” said Godwin Horebive. The substantive chairman of the community also told the newspaper in a phone interview that he made effort to arrest the contractor. “He then claimed the youth in the community attacked him and would not allow him to finish the project,” the chairman Edema Roland said. “Nothing like that happened.” He described the whole process as dubious.

But Noyivie Standard Investment Ltd showing up at Iyede Amei to slap together a load of bricks, and then cut out, can be no less dubious or wicked. Its integrity is even more at issue, considering how—with just a letterhead—it clinched the N23.9-million contract. The company wasn’t registered as of the time of the contract award in 2012. Besides, the contractor seems to know their number at the BPP and the NPHCDA. So bidding, winning, and defaulting couldn’t have been easier. “We have it on good authority that the contract was awarded twice and paid for twice,” Louis Oho told the National Daily in a phone interview. Oho is one of the leading political figures from Iyede Amei. Some of the villagers believe the sponsor, Hon. Ossai Ossai, and the contractor divvied up the money, and abandoned the project. The site has eventually become a wild outgrowth of weeds and banana clumps. Ossai was returned to Parliament so he can make the contractor complete the health centre, Oho said. Noyivie, however, isn’t planning to go back to work soon.

While the BPP has delisted the unregistered companies that participated in these biddings, this Agbor-based contractor morphed into Noyivie Constructions Ltd, and reapplied to the bureau. It’s now on the bureau’s Interim Registration Report—waiting for the next monkey business. A search through the CAC revealed the Noyivie clone was registered in 2003. So the unregistered Noyivie, its illegality, and the abandoned project have passed away.

When ethics matter, Iyede Amei should be the last village any contractor wants to rupture a health facility contract like this. The community is in the outback of Ndokwa LGA. A bike ride from the nearest junction along the Ugheli-Ogwashi Uku road takes 20 minutes to Ofakpe. You can get a grumbling commercial motorcycle operator to take you on the one-hour run through the dirt road to Ewo Okoroafor. A river, about 100-metre wide, flows fast but quietly here. And the Iyede-bound residents must cross it, to and fro, sick or sound. A carcass of a platform, which the locals call pontu, does the shuttle. It is worked by a rope moored on both shores, and tugged by three or more people to send the vessel adrift, with the help of the river currents. Pontu is wide enough to take 20 cars. It ferries humans and cargoes, including motorcycles, from shore to shore—for a sickeningly long period of 20 minutes or half an hour. That includes the waiting period, when just about anything bad can happen in case of health emergencies.

Oho narrated a case that eventually ended in death.

A boy was fooling around with a crocodile a neighbor was rearing at Iyede Amei back then. It happened the boy poked his fingers too dangerously into its cage. And the beast just snagged his tender hand. No first aid available. “Before they could carry the bleeding boy through the long ride [on land and pontu] to Ofakpe where there is a health centre, he died,’ said Oho, commenting on the mortality rate in his village.

There are auxiliary nurses whom pregnant women and others at Iyede Amei go to for help—at a forbidding fee, though. Alfred, whose house is opposite the abandoned PHC, said a nurse billed him N150,000 when his child had a machete cut. “If you complain,” he said, “they tell you, ‘Na you learn me school?” That’s broken English for: “How much did you spend on my training to make you determine my fee?”

Iyede is too far up-country to make their health plight, by reason of the contractor’s failure, known to the government. Distance and access alone are a problem, and even big enough to scare off a contractor bringing building material and equipment. But since Noyivie and other ineligible contractors came through the back door, chances are they never did the feasibility study as PPA requires—or they just took it for granted.

Some communities, still, were all too willing to understand this access problem, and were ready to help the contractors.

At Eyin Osun, for instance, you also have to cross the naked River Ogun to access the community—otherwise you have to take a longer route less travelled to come in. The villagers understood this, and made efforts in responding to Lonestar’s whining. “When the contractor complained about bad roads,” said Chief E.A Talabi, the chairman of the council of Eyin Osun baales, “we hired some labourers to widen the road to make it passable.” Then Lonestar worried about moving truckloads of sand to the site. “We told them not to worry,” the 80-something-year-old added. The villages mobilized, and dug into a river, and got out as much sand as the project needed. “We contributed money to buy the land for the project from the Ogunke Family,” he said, explaining all they did to encourage the contractor. “At a point, I brought my block-making machine to the site,” said Makaleta.

Still Lonestar would not come at all. It, probably, had some trick up its sleeves. The villagers the National Daily interviewed said the contractor had made the unsuspecting ones among the chiefs sign documents they didn’t understand, which might have indicated the project was completed. “They met the baales, took photographs with them, made them sign paper,” a woman explained. “You people should come during their meeting. You will hear stories about the contractor.”

Stories about the state of health and hygiene of Eyin Osun are, however, more important than Lonestar’s dirty deals. Luckily, Oriyomi, the only nurse in the community, confirmed only one pregnant woman, so far, died during childbirth. The only health centre the community built, just about three small rooms, all covered in grime, without tap water and toilet, is all the villagers, numbering three million, according to an unsubstantiated estimate, rely on. “If things go out of hand, we rush to Ijebu Ode,” said Bayo, a farmer and father of three from the Ogunke family.

The project sponsor, Hon. Kehinde Odeneye, was in the House back then. The villagers said he was always promising he would find out why Lonestar never showed up. But the honourable never got around to doing that till he left office.

Many of the sponsors of the projects the newspaper investigated didn’t come clean, really. Most are suspected to be promoters and backers of the unqualified contractors. And, for starters, sponsoring PHC projects isn’t the reps’ call to be made. The honourables are simply shirking their exclusive legislative duty by scrambling for such projects, according to Work Minister Babatunde Fashola

Many of the sponsors of the projects the newspaper investigated didn’t come clean, really. Most are suspected to be promoters and backers of the unqualified contractors. And, for starters, sponsoring PHC projects isn’t the reps’ call to be made. The honourables are simply shirking their exclusive legislative duty by scrambling for such projects, according to Work Minister Babatunde Fashola

“We must avoid the risk of crowded projects where legislators at the national level are made strictly to implement constituency projects that involve primary healthcare centres, which are for the local governments,” Fashola said. He was speaking at a summit the House of Reps and Conference of Speakers and the National Institute of Legislative Studies organised in May. Former Secretary to the Government of Federation Babachir Lawal also made some observation—that the scrambling was not just about representation—that it was about embezzlement. And constituency projects are the conduits.

As such, whenever the lawmakers lose re-elections, the pipes get blocked, and the flow of funds stops. Then nobody cares any longer about the projects. The reps so displayed this apathy their communities readily dismissed them as disinterested. Truly, there isn’t much in it for these politicians, especially since the communities refused to return them to the House.

At Okpara Inland, Ethiope, Delta, Hon. Emeyeson Akpoyogoga, who sponsored the PHC project there in 2012, is now a casualty of such voters’ revolt. He’s been shorn of his honour in that constituency.

The villagers said he abandoned so many projects in Okpara. The PHC is just one of them, and, indeed, a sight to behold: a mound of concrete floor chest-high, molding, inside a bush—since 2012. As usual, the story is that Akpoyogoga and Solazed International Concept shared the N12.1 million for which the contract was awarded.

That ends the story.

Okparaland is fairly big, estimated at about 20, 000 people. So the effect of the bungled PHC is hardly felt among its ordinary people. Many were not even aware. Stella, about 20, had her twins at the only health centre in Okparaland in July. She told the National Daily everything was okay. The matron there, Ephiede Omaveehrove, too, said they (just two of them) were doing their best. She added, though, if the new one had been completed, it could have eased their stress. She put the monthly delivery rate at around 26.

The Okparaland council of chiefs, however, took the failure more seriously. “We definitely needed the abandoned health centre. The federal government knew we needed it,” said Chief Unuero, the Otuta of Okparaland. The contractor, no doubt, cared little for their need. After the community gave Solazed land, the team, he said, came, introduced themselves “bountifully”, and, after that, left. “That was why he [the rep] lost.”

Former Hon. Bamidele Opeyemi lost his popularity, too, across Odo Uro, Iropora, and Araromi Obo in Ekiti. The villagers all over the 13 communities at Odo Uro even had more reasons to dismiss him. Deep inside the bush along the Ado-Iyin road, this community, a motley crowd of Urhobo, Igarra, Ebira, Tiv, Taraba, and Yoruba, suffers at least one cholera outbreak annually, said Tahir Lawan, who acted like the community’s spokesperson. “We have lost more than 10 pregnant women here.” It gets that bad because the villagers must take a 30-minute motorcycle ride to Ado Ekiti to see, at least, a nurse. Yet a PHC project started by Surjazz Ventures Ltd has been there since 2012. Nobody cares. “We have not seen Opeyemi since then,” said Ibrahim Umar, the village head. For the N9.5 million award, Surjazz only came, constructed a gate house, and a ward barely wide enough to swing a cat, and left. Umar said they never raised the issue with the former rep—perhaps because they are all squatters. Neither did they seek out Surjazz. How would they have even traced the unregistered company if they had wanted to?

Up that axis is Iropora, about 40 minutes from Odo Uro, along the Igede-Ifaki road. At the extreme end of the town lies another relic of the Opeyemi-sponsored PHC. It is a wide expanse of land. On it stand a rusty water tank, a big ward, unroofed, with its wooden raft exposed to the elements, and staff quarters the community itself roofed. No plastering, no fixtures. Everywhere bristles with weeds the villagers clear every now and then.

Maltec Construction Ltd, a company registered about the time of the contract award in 2013, is the contractor. “We don’t know them,” said HRH Joel Ajayi Olonibua of Iropora. And the sponsor they know is dodging. “Whenever we called Opeyemi who brought the constituency project, he would not take our calls.” The oba described Maltec as “unpatriotic and unfair to the community and the government that awarded the contract”.

Down at Araromi Obo, close to Afao, in Ifelodun LGA, lies another PHC project hemmed on the perimeter by an air-tight thicket of tall striplings. Breaking through that you hit a brick fence, and a gate, securing a small building, probably the ward, roofed, painted, standing in the middle of a cassava plantation. The gatehouse is even electrified—a make-believe. It is, simply, another uncompleted PHC. The handler, Kensessy Global Services, was not a legal entity when it got the N9.5 million contract almost five years ago. It has since gone off the radar. And the over 10,000 people the project could have been serving are helpless. “Even if we are angry,” says Faseluka Daniel, an elder in the community, “there’s nothing we can do.” Either to the contractor or Opeyemi.

Kensessy and all the defaulting contractors in Ekiti cut the picture of a saint when compared with the crookedness of their counterparts in Ogun. Of the six defaulting contractors, four—Lonestar and its unregistered corporate fellows Highrise Builders, La-Hipperson Nigeria Ltd, and Remza Global Resources Ltd—didn’t lift a spade on their sites.

Amongst these, Highrise Builders grabs the most eyeballs. The NPHCDA awarded it a contract worth N56.7 million, the second highest value in the southwest. The beneficiary of the PHC is Layaran Ajebo, a 10-roof community of bubbly locals inside a jungle in Obafemi Owode LGA. Small as it is, the community has an MDG health centre close by. And Strong Tower, a miner not too far from there, is building another one. That the contractor didn’t show up at all makes no difference to the villagers. They even refused to talk about it when the National Daily pressed them further for reactions to Highrise Builders’ irresponsibility. Same experience at Oke Agbo in Ijebu Igbo. There is no site at all here. Many of the residents still don’t know that Remza, a seat-of-the-pants construction company registered in 2010, was supposed to have completed a primary health centre worth N21.7 million since 2012. Apparently, there is no point fussing over that.

That was unlike the feeling at Mowe (Obafemi Owode LGA), a border town between Lagos and Ogun. A lot of the overflow from Lagos population pours in there, making it a fast growing community of about 40 villages. They need all the health facilities they can get. But HRH Adesan Olu Tajudeen, baale of Mowe, was disappointed. He told the National Daily there was no federal PHC there. The one abandoned there is a state project, and the functional one at Oja Agbesan, a market by the Lagos-Mowe expressway, was gifted the community. According to the baale, a young man had an auto accident along the expressway. There was nowhere at Mowe to take him even for first aid. Tajudeen said the boy’s rich dad then came back after the accident, helped complete the small community health centre building, and stocked it with drugs. La-Hipperson that got the federal PHC contract in 2012 didn’t even visit the community. Unregistered and ineligible as it is, the company knows its way around the BPP and NPHCDA. It got two slots that year. The other one was supposed to be at Oke-Ogun, in Oyo. Both were N6.4 million a slot. Nothing is in sight now—contractor and all.

In Lagos, Eko Dabra Nigeria Ltd, one of the three unregistered bidders in the state, got the NPHCDA contract in Eti-Osa, Oriade LCDA. It, however, failed to deliver on its N32.3 million project, and still got shortlisted for 2015. Adjustment Resources Nigeria Ltd (Eti-Osa, Ajah PHC) and Laide Biz Ventures(Agege PHC) also failed on theirs worth M18.4 million and N23.8 million respectively.

Conway Nigeria Ltd was the only inexperienced contractor on the failed PHC projects in the state. It was not only registered in 2011 for the 2012 project; the company also gave to the CAC someone else’s home address as office. Was the occupant surprised? “No, no, no. This is a home. Nothing like Conway here,” the gatekeeper at 49, Gana Street, Maitama, Abuja, told the National Daily.

The Collusion

That forgery is corruption, by the SBD standard. But it is no big deal. The BPP has brought Conway back under a new complexion—Conway Contractors Ltd. Eight other unqualified contractors are back, too. Among them are Sure Delivery Nig. Ltd, Martex Integrated Concept Ltd, and three others. The three—unregistered, and inexperienced contractors—Centenary, Akaba, HighRise Builders—didn’t break much sweat on their project sites. They are now sitting pretty on the bureau’s IRR list. A December 11, 2014 circular from the office of the SSG stated the contractors IDs would serve as “evidence of registration” for securing new contracts from the MDAs.

Unregistered ones like Noyivie Standard Construction and Centrestage Global Venture Nigeria Ltd have also changed their names: Noyivie Construction Ltd and Centrestag (typer’s devil!) now appear on the IRR list. Gerald Frank Nigeria Ltd made the cut, too—still unregistered as it was five years ago when it got the first N13.2 million PHC project at Fugar, Edo.

BPP’s new helmsman Ahmadu would not respond to questions mailed to the bureau—about unregistered companies who brazenly abandoned their projects but are now on the national contractor database. And it has given no official information on its effort to even look at who got what of the billions wasted on the PHCUOR. No ass has been kicked for the rules violated either.

But the PPA is clear on this.

Sections 6d and 53 prescribe investigation of breaches like these. And in case a criminal probe is necessary, the EFCC or ICPC can come in. Section 28 of the ICPC Act 2000 empowers the anti-graft commission to butt in on such cases.

In December 2013, the commission actually invited 368 contractors that were awarded PHC contracts between 2006 and 2012. No fewer than 17 of the unregistered and incapable contractors the National Daily investigated were among the second batch the commission questioned then—for their 2012 abandoned projects. The ICPC investigator the newspaper sought clarification from wouldn’t respond to questions on the outcome of the investigation. And from the N1.9 billion the commission claims it made between 2006 and March this year, no amount, in the document published on the ICPC website, is marked as recovered from NPHCDA failed contractors.

So none of the 2012 contractors has been prosecuted—not to mention those of 2013 and 2014. Yet for Highrise Builders and 56 others forgers and bid-riggers who won contracts which they eventually abandoned, the PPA prescribe a punishment: a jail term of five calendar years but not more than 10 years without an option of fine. Their directors, as listed on the CAC, are to be jailed for three years, but not exceeding five—without an option of fine. The companies also are to pay a fine equal to 25 percent of the contract value. That’s about N136 million for those 57 quacks. And they shall be delisted as government contractors for five years. Eight of them, however, are back again on the IRR list.

As the illegal contractors are clean gone, their NPHCDA and BPP co-travellers are also feeling cool now, home and dry, after taking the risk to shakedown the government. By the PPA recommendation, they ought to have been suspended, removed, or dismissed from government service. Or they should have bagged a jail term of not less than five calendar years, but not more than 10. No option of fine.

But nobody seems ready to crack the whip. And the consequences are grave. There is no doubt about where the primary healthcare system is heading: south of course.

That, however, is no news. Nigeria has gone that familiar road several times. Primary health policies have been collapsing since 1978. It is just that many believe lightning doesn’t strike a place twice. But this is one more time contractors will be responsible for this failure. The immediate past Health Minister Eyitayo Lambo recalled how the Basic Health Services Scheme (BHSS) implemented between 1975 and 1980 also went down like a lead balloon thanks to contractors.

“Most of the buildings were not complemented. Medical equipment was delivered but remained unused for many years (if ever),”he said in his presentation at the NPHCDA first annual lecture in Abuja in 2015. “Individuals and companies were paid for equipment that was never delivered, and for work that was never done.” The consequence was just as expected. “No primary health care service was being delivered in any part of the country,’ he said.

Thirty-seven years have made no difference. Nor the billions spent so far. The PHCUOR’s N8.9 billion is just 29.2 percent of the total amount, N30.5 billion, the government spent on PHC construction between 2001 and 2014—to control epidemics, malnutrition, mother-child mortality in rural areas, among other objectives. All of that may have gone down the toilet. “Every single day, Nigeria loses about 2,300 children under five and 145 women of childbearing age,” UNICEF’s 2016 report revealed. “This makes the country the second largest contributor to the under-five and maternal mortality rate in the world.” The 2017 report shows some bounce:1, 350, the world’s third largest. That is still unacceptable, Health Minister Isaac Adewole said. And, in terms of overall healthcare delivery, Nigeria ranks 187th among 190 countries in WHO health care delivery system.

The ranking will get no better soon. Because Iyede Amei and Orere, in the belly of Delta’s mangrove forests, still live in unhygienic conditions, and consult witch-doctors as birth attendants. And Noyivie and Akaba, the charlatans that short-changed them, remain holed up in the BPP and NPHCDA that sacrificed Nigeria’s latest primary health policy.

This investigation is supported by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation and the International Centre for Investigative Reporting.

Trending

Football2 days ago

Football2 days agoGuardiola advised to take further action against De Bruyne and Haaland after both players ‘abandoned’ crucial game

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoDollar crashes further against Naira at parallel market

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoRecapitalisation: Zenith Bank to raise funds in international capital market

Education1 week ago

Education1 week agoArmy reveals date for COAS 2024 first quarter conference

Crime1 week ago

Crime1 week agoFleeing driver injures two on Lagos-Badagry expressway

Covid-191 week ago

Covid-191 week agoBritish legislator demands Bill Gates, other ‘COVID Cabal’ faces death penalty

Latest5 days ago

Latest5 days agoIsrael pounds Hezbollah with airstrikes after Iran attack

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoZenith Bank surpasses N2trn earnings milestone