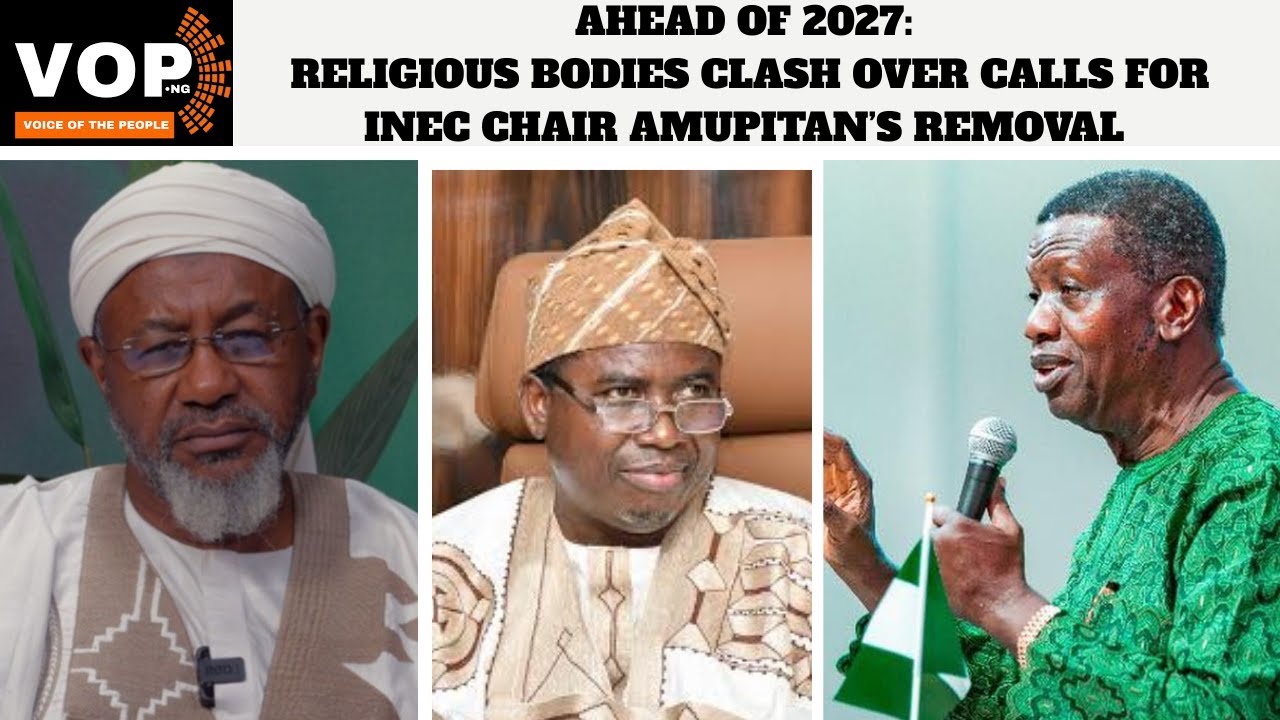

When the Supreme Council for Shari’ah in Nigeria (SCSN) last week demanded the removal and prosecution of the Chairman of the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC), Prof. Joash Ojo Amupitan, the reaction was swift, emotional and deeply polarising.

In a country where religion and politics often collide, the call was immediately framed by critics as a sectarian attack.

But the Council insists that narrative misses the point entirely.

According to the SCSN, its position has nothing to do with faith and everything to do with integrity, neutrality and the survival of national unity at a critical moment in Nigeria’s democratic journey.

The controversy stems from allegations that Prof. Amupitan authored a legal brief in which claims of persecution and genocide against Christians in Nigeria were reportedly affirmed. The Council argues that such a position, if left unaddressed, undermines the impartiality required of the nation’s chief electoral umpire.

The backlash was intense. The Christian Association of Nigeria (CAN) in the 19 northern states and the Federal Capital Territory criticised the SCSN, warning against turning religion into a political weapon and deepening divisions in an already fragile polity.

In a statement dated February 2, the SCSN said its resolution was reached during its Annual Pre-Ramadan Conference and General Assembly held on January 28, 2026, but was later misconstrued and amplified out of context.

“The Council states unequivocally that its position is not motivated by religion or sectarian considerations, but by grave concerns relating to national cohesion, institutional integrity and constitutionalism,” the statement read.

To underscore its argument, the Council turned to history. Since Nigeria’s independence in 1960, it noted, the leadership of the country’s electoral institutions has been dominated by Christians—without resistance from Muslims.

“From Eyo Esua in 1964 to date, the overwhelming majority of those who have headed Nigeria’s electoral institutions have been Christians. Of the thirteen chairmen who have led the Commission, only two—Prof. Attahiru Jega and Prof. Mahmood Yakubu—are Muslims,” the Council said.

“At no point have Muslims mobilised opposition against any chairman on religious grounds. All were accepted on the basis of institutional legitimacy, not faith.”

READ ALSO: Female voters outnumber men as INEC registers 36,638 new voters in Gombe

For the SCSN, what sets Prof. Amupitan apart is not his religion but his record. Central to its concern is a legal brief allegedly authored by him in 2020, which the Council described as toxic, provocative and deeply prejudicial against Nigerian Muslims and Northern Nigeria.

Particularly troubling, the Council said, are claims of a so-called Christian genocide in Nigeria and attempts to link present-day insecurity in the North to the 19th-century jihad of Sheikh Uthman bin Fodio.

Rejecting the genocide narrative, the SCSN argued that insecurity in Northern Nigeria is complex and indiscriminate, affecting both Muslims and Christians.

“Available data show that Muslims constitute the majority of victims in states like Borno, Yobe, Zamfara, Katsina, Sokoto and others. Advancing a one-sided persecution narrative is intellectually dishonest,” the Council said.

Beyond the substance of the allegations, the Council said what deepens public concern is the absence of denial, apology or retraction from Prof. Amupitan since the controversy became public. It added that the Federal Government has reportedly had to counter the claims internationally, resulting in reputational and financial costs.

Speaking on the matter, the President of the SCSN and Imam of Al-Furqan Mosque in Kano, Dr Bashir Aliyu Umar, was emphatic that religion is not the issue.

“It is not about religious affiliation,” he said. “It is about integrity and the ability to rise above issues that will compromise a person’s sense of judgment.”

Dr Bashir stressed that the Council is not a political party but an advocacy body speaking, in its view, on behalf of millions of Nigerian Muslims.

As the debate intensifies, support for the SCSN’s position has grown in some quarters. A former Kano State House of Assembly aspirant, Mukhtar Adnan, said the INEC chairman could no longer be trusted to oversee Nigeria’s elections.

As Nigeria inches closer to another round of high-stakes elections, the controversy has laid bare a fundamental question: in a deeply plural society, how much past conduct is too much for an institution built on trust, neutrality and belief in the ballot?

Football1 week ago

Football1 week ago

News7 days ago

News7 days ago

Comments and Issues1 week ago

Comments and Issues1 week ago

Comments and Issues1 week ago

Comments and Issues1 week ago

Comments and Issues1 week ago

Comments and Issues1 week ago

Latest1 week ago

Latest1 week ago

Comments and Issues1 week ago

Comments and Issues1 week ago

Comments and Issues1 week ago

Comments and Issues1 week ago