Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko has announced that Wagner Group leader Yevgeny Prigozhin is back in Russia, despite the oligarch-turned-warlord’s widely reported deal with the Kremlin to accept exile in Belarus after the June 24 rebellion.

The Belarusian dictator had said on June 27 that Prigozhin—who has long been close to Lukashenko—had arrived in his country as part of the deal to end the brief Wagner uprising against the Defense Ministry, in which mercenaries seized the southern city of Rostov-on-Don and even threatened a march on Moscow.

On Thursday Lukashenko said : “As for Prigozhin, he’s in St Petersburg. He is not on the territory of Belarus.”

The Wagner chief has reportedly been seen in St Petersburg and Moscow in recent days, as he negotiates with the authorities over the dissolution of commercial interests in Russia and the return of assets—including more than $100 million in cash and gold bars—seized by investigators after the mutiny.

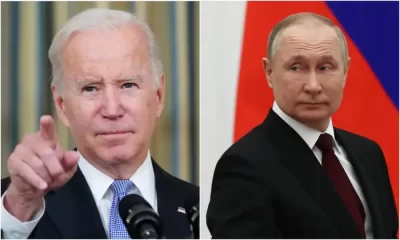

Lukashenko’s remarks pose a problem for President Vladimir Putin and his top officials, who quickly defeated the Wagner revolt but were unwilling or unable to hold Prigozhin to account for what Putin initially described as “treason.”

ALSO READ: Wagner group remains deadly threat to our state, says Putin

The news comes as Russian President Vladimir Putinhas set out to neutralize future threats to his power by reining in the Wagner Group amid the Ukraine war and empowering a new security apparatus.

The consequences of the aborted mutiny appear to be worse for Prigozhin and his Wagner group than for the Russian elite. Analysts see a brokered deal as an attempt to salvage the military’s potential for conducting offensive operations in Ukraine. However, some of Russia’s assault-capable groups are likely to be broken up due to political concerns. “They’ll be reassigned to separate units so that the leadership in Moscow no longer has to worry about any repeat insurrectionist tendencies,” Russia analyst George Barros told Newsweek.

What happens now? Wagner’s operations encompass far more than Ukraine, and it remains unclear what will happen with fighters stationed in Syria and elsewhere. Although a private military company, Wagner has depended on support — equipment, fighter jet pilots, and others — from the Russian state. Whether or not its fighters far from home will continue to receive such support is yet another unknown. Meanwhile, the capacity of the Russian government to subdue these fighters abroad has been constrained further due to the resource demands of the war in Ukraine.

Latest5 days ago

Latest5 days ago

Trends6 days ago

Trends6 days ago

Business1 week ago

Business1 week ago

Football1 week ago

Football1 week ago

Health7 days ago

Health7 days ago

Football6 days ago

Football6 days ago

Featured1 week ago

Featured1 week ago

Business1 week ago

Business1 week ago