Featured

Mr. Goody

Published

2 years agoon

By

Editor

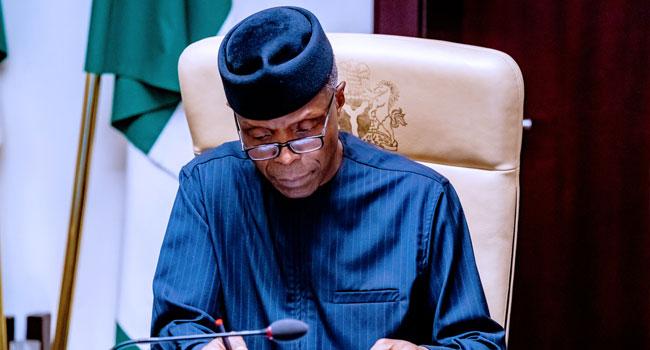

With Pentecostal brio, and a quiet belief in foreordination, Osinbajo took the plunge into the vicious water of politics in 2014. Where the tide of ambition carries him in 2023 is just your headache

Olusegun Elijah

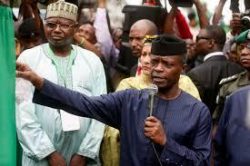

The crowd surged at Yaba Bus Stop that morning in 1995. Stern-looking soldiers in their leafy-green camouflage, hugging their AK-47s, took position, alongside scores of police men. Hordes of protesters poured in with their placards, and the mob thickened, especially because it was that part of Lagos—the part where activists of that perilous time favoured to spark up public outcries. The organisers of the rally—the Concerned Professionals—equally rolled in, armed with only English language and rabblerousing rhetoric, shadow-punching for a protest against the military President Gen Sani Abacha (late). It was suicidal for any one resisting the sadist. And this motley group of engineers, lawyers, journalists, writers, medics, and others thought they had enough balls to confront Abacha.

Among those dicing with death that day was a 38-year-old. He was just about 5 feet tall, a damn good speaker, father of one in a family as young as six. He was, then, a professor at the University of Lagos, bubbling with ideas of how to change Nigeria, and looking for a vent for all the brainwaves he carried about in his big head on his young shoulders—everyday.

That day, at Yaba Bus Stop, remains etched on his mind till date. As it turned out, the Concerned Professionals had other concerns.

Fate, however, had a date with that young professor.

Yemi Osinbajo, 21 years later, found himself thrust into a position where he could embody his youthful chimeras, as the vice president of the Federal Republic of Nigeria.

But wishes are no horses.

Those dreams are still there, penned up. His position as the sidekick to a bone-old president makes him subject, constitutionally, to things he has no control of. Many Nigerians believe he’s just a fixture at Aso Rock where a clique of President Muhammadu Buhari’s men toggle the veepee about.

Osinbajo is not complaining. The APC government critics, however, are. They urge him daily to dig in his heel, take on the cabal, or resign. In an interview with a newspaper, Mike Ozekhome, a senior lawyer, gave the vice president two nuggets. “The first option is to get ready to pull his punches and fight like a man that has a manhood,” he told the Daily Independent. “The second option is that he should honourably resign before they pour more ashes on his head and bespatter his white garment with more mud and excrement.”

Well, Osinbajo is no pushover who needs such counsel of perfection. He knows his onions about the office he holds. He told this story of how he and candidate Buhari were on their campaign trail in 2014 in Zamfara. Something struck Buhari about the crowd thronging them. “They expect that by the second day when we take office, we must solve all their problems,” Buhari told Osinbajo

“I said to him, ‘That is what they expect of you—not me!’ ”

According to Osinbajo during his speech at the 2017 summit of the Institute of National Security Studies, that exchange kept coming up between them. Even if his response was a joke, it got close to the bone. And its finer point makes sense: the responsibilities, the burden to fix Nigeria are Buhari’s cup of tea.

The vice president doesn’t mix it with anybody when it comes to this division of labour at Aso Rock. No matter how bright his ideas sparkle in his greying head, his role, he knows, is merely representative—and polishing the apple. And he does that gushily. Anywhere.

“I want to thank His Excellency, the President of the Federal Republic of Nigeria, President Muhammadu Buhari, for giving me the opportunity to coordinate this programme and also for giving me a free hand to run the programme,” Osinbajo said of the Social Investment Programme in one of his speeches in 2017.

Such complimentary lines form the meat and potato of his speeches and remarks. He doesn’t mind if it’s all he does—or just about the only aspect of his contribution he permits himself to flaunt. Stacked on his personal website, as Clear Thoughts from the Office of VP…, is a hagiography of more than 300 speeches he gave wherever he had the opportunity in four years of standing in for—and flattering—his boss.

Even when he became acting president in 2017, while Buhari was a downer battling for his life in London, Osinbajo still acted in the shadow of his boss. “There is very little that is done without the President’s clearance and endorsement,” he told newsmen when Buhari finally resumed. “Even with some responsibilities that are mine constitutionally, we always have full discussions and agreements on them.”

With airs and graces of a grateful steward, he described all this fawning with the finest word: teamwork.

And those who recognize—and appreciate—loyalty have always given him the backrub he deserves. “Prof. Osinbajo is the most honest person and leader Nigeria has produced in recent times,” said HRH Farouk Umar, emir of Daura where Osinbajo went to represent his boss during a turban ceremony Nov. 3. The V.P., a southwesterner, didn’t just become the bomb in Buhari’s northwestern hometown. There was a reason. “I am particularly happy with the vice president for the way he has shown loyalty to President Buhari.”

Loyalty is one thing Osinbajo has in abundance. Other than being a brainbox, he has nothing much qualifying him as a politician. No antecedent. No structure. No political ideology. His spiritual mentor and General Overseer of the Redeemed Christian Church of God (RCCG) Pastor E.A. Adeboye testified Osinbajo never thought Aso Rock was beckoning. “He was not a politician.”

If Osinbajo plays politics at all, he does it with one thing he practises well: being as faithful as a dog. It is loyalty that paves the way for his ingenuity which has been propelling him politically since 1999 when APC’s national leader Bola Tinubu, then a governor and crack headhunter, discovered him. He heaved up Osinbajo from classrooms to the office of the Lagos attorney-general—for two terms.

That loyalty also lucked him—wet behind the ears as he is among the litters off newbies in the southwestern realpolitik—into being the only fave Tinubu could nominate as Buhari’s running mate in December 2014.

Osinbajo himself described the push as unexpected. That response further peeled back the veneer, and revealed something more about the vice president: no inordinate ambition.

His detractors, mostly his kinsmen from the southwest, Femi Fani Kayode and Festus Adedayo, among others, however, contest that. Especially Fani-Kayode who seems Osinbajo’s bitterest household enemy. In gall-dripping articles, FFK (he didn’t answer questions on whether it is out of personal hatred) frequently hurls at him a blitz of stinkers: poisonous dwarf; weak; lily-livered; half man; short-man devil; slave-man. The PDP sparkplug also doubts the vice president’s integrity. “Does loyalty to his principal mean he must betray his people and his faith and violate his oath of office?” he wrote when Osinbajo asked Nigerians to pray for violent Fulani herders. Among those the vice president has betrayed, FFK wrote, are the late Obafemi Awolowo, Tinubu, Adeboye, CAN President Samson Ayokunle, and the Afenifere.

No question about why Osinbajo’s attackers get this offensive nowadays. He’s become fair game. Series of shake-ups that rocked the presidency recently, in Buhari’s absence, saw the office of the veepee badly ruffled. Thirty-five of his staff were elbowed out—or redeployed; the SIP he executed so well he became ghetto-famous was ripped away from him; his chair of the National Economic Council was yanked off, and the body re-organised to deal directly with the president; and Buhari stopped transferring power to him whenever he is out of the country on short terms—which was not so before.

“Does loyalty to his principal mean he must betray his people and his faith and violate his oath of office?”

All these happening in a flurry, and their impact on the representative role he has even accepted drove conspiracy theorists and truthers into a frenzy. Some reconstructed the scenario, and puzzled out a rift between Osinbajo and Tinubu. As it went, Tinubu was nursing the 2023 presidency, and was scared shitless his godson was stealing his thunder. So the godfather got henchmen in the trio of Buhari’s CoS Abba Kyari, his cousin Mamman Daura, and ally Babagana Kingibe.

Others spun the yarn of the cabal working for another presidential wannabe from the north—Kaduna Gov. El Rufai who wanted the path cleared for him to succeed Buhari. So the rising star Osinbajo had to be dimmed in any way possible.

Some said Buhari was angry with his vice president for taking certain decisions—like confirming former CJN Walter Onnoghen—as acting president in 2017.

The riot of tales worsened because the veepee is a Christian. The theorists insisted the ruling north, predominantly Muslim, would never allow a Christian to succeed Buhari. The Christian Association of Nigeria also muscled in at a point—in solidarity with their own man taking hits in a government it believes is Muslim-heavy.

Osinbajo, as always, said no rift—either between and Tinubu or Buhari. And neither of the two admitted they had a problem with him. Many will dismiss these denials as politics. Lying. Cloak-and-danger games. If Osinbajo were a politician, maybe he could play at such. That is to say he’s contented with what he is now: a second John, a born-again Christian (pastor). And he would get where he wants, by some divine appointment, without playing hardball.

Osinbajo, apparently, is having a blast playing the second fiddle—if one disregards the tribulation of the theorists and the Aso-Rock cabal. For instance: He holds a nightly gig every Independence Day in Nigeria. The white-tie event gives him a chance to display the stuff that makes him Buhari’s vice president: rib-cracking orations delivered in a manner both creative and scholarly—about his boss and their fatherland. With the aid of Power Point and projectors during the last October 1 dinner, he described Buhari as the swankiest president Nigerians would ever have. A prized storyteller, trying to drive home his point, on another occasion, about the amount of optimism pulsating in Nigerians’ veins, the vice president unspooled another slice of life. It was about his former driver—a father of 14, a perpetual broke-ass. According to the V.P, the driver said he kept making babies because he hoped one of them would become Nigeria’s president. At another hilarious moment, at the Eagle Square, after his party’s national executive election, Osinbajo compared the height of the outgoing chairman John Odige-Oyegun with the incoming Adams Oshiomhole’s. Then, as introduction, he told his audience waiting to hear him praise his boss: “By [Oshiomhole] succeeding the much taller Chief John Odigie Oyegun, I think the APC has finally achieved the long and short of the matter.” He earlier declared himself chairman of an APC committee whose members include El-Rufai, Oshiomhole, Labour Minister Chris Ngige and then Health Minister Isaac Adewole. “[These are] vertically humble, gentlemen who have refused to show off by ensuring that they maintain modesty in their heights,” he said.

That’s a typical punchline from Osinbajo on the soapbox. What more can an orator of a vice president, choked up by succession politics amidst a cabal, ask for?

Adedayo, Fani-Kayode, and other critics hacking at him may do all they can in their navel-gazing—about him, and his 2023 ambition. It’s no skin up his nose. At 62, besides the gift of health, he told journalists, he already counted himself fulfilled.

Why wouldn’t he—looking at the charmed life he has lived. He swept the board throughout his secondary education at Igbobi College, Yaba, Lagos; he moved on to UNILAG to study law; and he later went to the London School of Economics and Political Science for his Masters, becoming the first hotshot in law of evidence in Nigeria. His career has moved through Nigeria’s public service—as a varsity lecturer, and an AG Lagos—to the global level—as a consultant to the UN. He notched up most of these achievements in his 30s. He co-founded the Business Integrity, the Orderly Society Trust, the Justice Research Institute, and founded the Liberty Schools Project, a do-gooding concern for the have-nots in Lagos.

Like most success stories, Osinbajo believes he owes mankind this debt of making the world a better place. He could be stretching his luck thin with such smugness; but the Messianic feeling it offers can be irresistible. He, once, let it slip during a speech.

“All my adult life I have always believed that our country is performing far below its potentials,” he said during his presentation at the 2017 edition of The Platform, a talkshop the Covenant Christian Centre organizes in Lagos annually. “I believed and continued to believe that the Nigerian people deserve better lives.”

His belief could just have been reinforced by his Christian faith. His is a sort of faith that tempts anyone so devout to believe they are the only good thing that just happened to the most populous black nation on earth—even when they lack the political means and ways to make the faith work. Miracles, prophecies, predestination—Osinbajo, a pastor in the RCCG, believes in them all.

He actually got one, from South Africa. He was sitting in the pew at the House of Revival Church, in Brakpan, in 2013 when a prophecy came—that he would be vice president of Nigeria. “I didn’t take it seriously,” he told the congregation when he went back there in Oct. 2015, as Nigeria’s No. 2 citizen. Now he believes. “God doesn’t look at size,” he added.

Perhaps Osinbajo has been tempted to take himself seriously on that account. After all, he too is flesh and blood, in spite of his storied integrity. And he knows a thing or two about integrity and human foibles.

“As human beings, we must admit the possibility of occasional failings or infrequent episodes of poor judgment; even more so a group or community level,” he told his audience at the third annual Christopher Kolade Lecture on Business Integrity in Lagos in June 2015.

For now, no one knows if the veepee has given in to the subtle prodding of ambition to save Nigeria in 2023. Those afraid of him, those angry with him, and those enamoured of him (for just his hyperactive concern for Nigeria) can only guess. The odds are high they are well off the mark.

But for Osinbajo to endure the next three years amid this cesspool of suspicion seems another confrontation. It is different, though, from his Yaba Bus Stop experience in 1995 when he and his concerned professionals showed a clean pair of heels at the first boom of guns. The repression this time requires no boots on the ground. He is taking on an array of political foes, and his concern now will focus on saving his integrity—not Nigeria.

First published December 12, 2019

Trending

Football6 days ago

Football6 days agoGuardiola advised to take further action against De Bruyne and Haaland after both players ‘abandoned’ crucial game

Health & Fitness16 hours ago

Health & Fitness16 hours agoMalaria Vaccines in Africa: Pastor Chris Oyakhilome and the BBC Attack

Aviation1 week ago

Aviation1 week agoDubai international airport cancels flights as flood ravages runway, UAE

Featured5 days ago

Featured5 days agoPolice reportedly detain Yahaya Bello’s ADC, other security details

Comments and Issues6 days ago

Comments and Issues6 days agoNigeria’s Dropping Oil Production and the Return of Subsidy

Education5 days ago

Education5 days agoEducation Commissioner monitors ongoing 2024 JAMB UTME in Oyo

Business5 days ago

Business5 days agoMaida, university dons hail Ibietan’s book on cyber politics

Education1 week ago

Education1 week agoOsun NSCDC solicits cooperation towards national assets protection

Pingback: Mr. Goody - National Daily Newspaper - Top Naija Headlines

Pingback: Mr. Goody - Highly Suggested