Crime

IBARAPA: The Whirl before the Storm (3)

Published

3 years agoon

By

Editor

Because it fizzled out fast, the small war in Ibarapa seemed a trifle. Not at all.

By Segun Elijah

Graphic content below. Readers discretion advised

Other Yorubas in the Fulani criminal underworld in Oyo might not be goading cows into browsing crops on people’s farms (Ogundijo Joseph); they might not be setting plantations on fire and uprooting cassavas (Ayinla Aderogba); they might not be slashing farmers’ skulls (Mrs Jamiu Tawa), chopping green fingers off (Mrs Muibat Taiwo), and firing dane guns at land owners. All these are marks of violent Fulani herdsmen that Adeogun, LAREG, and others documented in Ibarapaland over the years. These Yorubas, however, formed a small percentage of the mushrooming Fulani criminal rings kidnapping and killing in Ibarapa.

These groups used more brutal modes of operation: Ak-47 guns sometimes, cold-blooded murder of hostages even after ransoms.

According to LAREG’s spokesperson, one of the two suspects in another incident that flayed nerves at Lanlate—Modupe Oyetoso’s fiancé’s murder—was a Yoruba man. The gang ambushed the couple returning home after the day’s work on their 5000-hectare farm last August. The kidnappers shot, and the bullet hit his skull, the lady narrated. She identified the gang members (who later kidnapped her) with their build, dressing, their Fulbe-intoned Yoruba language, and their ‘long-barrelled’ guns.

To know which Fulani criminal group—violent herder’s or kidnap bandit’s—carries which gun, illegally, has been generating controversies in Nigeria. “I have never seen Fulani herdsmen armed with AK-47s,” LAREGs spokesman said. “Only those who came under fire—or were kidnapped by gunmen—could tell.” Oyetoso, a graduate of the Polytechnic, Ibadan, couldn’t have missed an AK-47 if she had seen one in the days she spent in Fulani bandits’ captivity.

The Ogunlanas too came under fire from a kidnap ring. The spent bullets the police extracted from the car were analysed. “According to the police, the gun that penetrated my car was suspected to be AK-47,” Gabriel said.

Akowe Agbe’s medical partner Oyewusi could tell, too. He could have documented the number of AK-47 bullets he extracted over the years. But he wasn’t reachable. He didn’t respond to enquiries sent to his phone, either.

Something confound many Nigerians about this caliber of guns and its proliferation down south. One: there’s misinformation with photos of AK-47-armed herders on the Internet. Many of them had been fact-checked as originating from Kenya—or those of armed Bororo women, from Sudan. Two: the cost could make proliferation difficult among common criminals. A unit of AK-47 shipped in from Burkina Faso, Nigeria’s major supplier, goes for N700,000 to N800,000, a gun runner, Olugbenga Ojoomo, arrested in Oyo in 2019, explained. “The truth is that they [Fulani herders and robbers] cannot afford to buy from us,” he said. They either steal from those who bought from gunrunners or rent it from police officers, political thugs, retired military officers, and others. “Except high profile kidnappers who will disguise as a responsible person.”

But, AK-47 rifles or not, Fulani bandits could be very ruthless on their targets—the rich—even with machetes.

Their brutal murder of Dr. Fatai Aborode actually set Igangan afire. A returnee from Germany, he went into cashew cash-cropping on a large scale in his hometown. Aborode also represented Ibarapa North in the House of Reps in 2015. “His farm covered at least 1,000 hectares,” Asigangan said. “And he employed our youth working for him.”

His murder spawned different versions of the circumstances leading to his death last December. Some said he was killed in an ambush while coming from the Salihus—to whom he went to report herdsmen trespassing on his farm. But his farm manager kidnapped with him debunked that. In fact, Aborode, he said, was on a most friendly term with the herdsmen around his farm. It would have been a kidnap and ransom (K&R) case had the bandits demanded money. They didn’t. The manager simply described them as four “gunmen”. The Oyo police command said they were robbers. But Igangan farmers insisted they were Fulani herdsmen. “They knew his cashew plantation would definitely make grazing impossible for their cows,” Adeagbo said, explaining how he went to court to obtain a restraining order against the herdsmen for Aborode.

On the day of the attack, Aborode and his farm manager were ambushed on their way home. The killers took him some distance away from his manager, and fatally slashed him with a machete. No reason given. “The Fulani just hated him and wanted him dead because of his success,” said Asigangan.

The average Nigerian could understand why the criminals were ethnically profiled in the Aborode murder. There were stewing hostilities between Yoruba and Fulani in Ibarapaland. But, as it happened, the Fulani themselves were not spared the scourge of their criminal tribesmen.

Alhaji Salleh at Ago Aare was kidnapped last year. Aliyu said the kidnappers demanded N6 million because they knew Salleh could pay. He did. “But after they collected the N6 million, the bandits killed him.”

A Fulani victim didn’t even have to be as rich as an Arabian merchant before the kidnappers snatched him in Ibarapa.

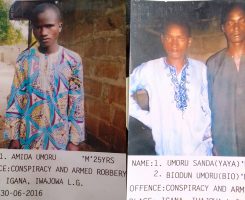

The Umorus , Fulani suspects arrested at Igana

The JNL spokesman shared the story of the ordeal one of them went through. Alhaji Jidda wasn’t a picture of wealth or health as he sat on the mat inside the now gone stall at Eruwa Feb. 8. He looked sapped and willowy, and, probably, at a loss as Aliyu spoke in Yoruba (Aliyu, 40, married a princess in Ikare Akoko) telling Jidda’s story.

“When he first told us someone called and threatened him with death if he didn’t bring money, we dismissed it as a prank,” said Aliyu. But the caller was unrelenting. “So we advised Jidda to run for his life.” He had nowhere to run—just like Aliyu born and raised in Ibarapa East by parents who migrated to Ipako, Oke Ogun, in 1968. Even in Igangan, bad as it was, some of the Fulani men there knew no other town all their lives. Some had Igbo-Ora blood flowing in their veins. “We called this generation of Fulani Abaku,” said Adeagbo. They had nowhere to run, either.

So out of fear, Jidda ponied up N300,000—to redeem his life from the hands of his criminal tribesmen. After all, his own affliction was lighter compared to others’.

Alhaji Hanji was kidnapped twice because he couldn’t pay the N3 million his kidnappers demanded at once. Alhaji Saman paid his N2 million ransom, but the abductors broke his leg before letting him off.

All these happened to both the squatters and the hosts in Ibarapaland in what Aliyu described as peace time. If the hostilities boiled over eventually, anybody could tell the consequences—bad. Or even worse, considering government failure most people complained of.

A frustrated Adeagbo had to show a local government chairman, Hon Okedeji Segun Daniel, the length of his tongue once. “I told him how Fulani herdsmen were committing atrocities on our farmlands in Igangan, and how Salihu was asking us why we planted crops there. And the chairman said, ‘What kind of atrocities?’”

“You must be stupid!” Adeagbo fired back.

Okediji wouldn’t respond to a request for clarification of these allegations.

“You see. That was how our political leaders and traditional rulers sold us to Fulani in Ibarapaland,” Adeagbo said.

Even Makinde was no exception. “I will never forgive him for saying the Fulani crisis in Ibarapaland was exaggerated,” LAREG’s spokesperson vowed. The governor didn’t visit, call, or showed concern in the Aborode and Oyetoso incidents, he added. “It’s either our state government is covering its failure to protect its people or state government is condoning criminality for personal gains,” Ogunlana, too, insisted.

But Adeagbo would like to spare Makinde because the problem predated his administration. (LAREG’s spokesman said he knew about farmers and herders clashing as far back as when he started learning arithmetic.} Akowe Agbe, however, lambasted the police and Amotekun security network. They were all compromised, he believed.

“Our butchers here just told us some Bororos, on their way out, handed over the cattle of the Ibarapa North Amotekun coordinator, Akinloye Oyebisi, to them,” he said. The administrative officer at the Eruwa branch of the outfit resisted all attempts to seek clarification on Feb. 7. “We know the security people can’t do justice, no matter the efforts put into it.”

Before, Fatai Owoseni, a former police commissioner now security adviser to the governor, urged the 33 LGA chairmen in Oyo to hold periodic security council meetings. Adeagbo explained how that turned out: every month, the chairmen in Ibarapaland would just call the serikis, imams and reverends.

“They’d come together to eat and drink, and share the LGA security votes. No farmer or hunter would be invited,” Adeagbo said. (Again, he had no evidence of the money-sharing.) “Are the Quran and the Holy Bible what we need to end Fulani violence in Ibarapaland?”

It was certain Akowe Agbe and Igangan people would, someday, run amok, and evict those they called Fulani-Bororos. Their town had become the hotbed of Fulani criminalities in Oyo. And that was because of its closeness to Niger Republic and Togo, where cross-border Fulani bandits could easily slip in, said LAREG’s spokesperson. But that was no reason to hound Nigerians out of anywhere in the country. “We’re all Nigerians. There are southwesterners in the north, too,” he said. “We just have to take a holistic approach to solve the problem.”

Ibarapa East had been powwowing with all the groups and communities in the area. And the consensus reached, at least, constrained the Fulanis to never mull reprisals. That tolerance could still keep the heat at room temperature. Based on intelligence it gleaned from the Fulani herders, LAREG also suggested allowing the Fulani to track the criminal elements among them. “They know one another,” the spokesman said.

On the eviction, Igangan maintained its initial hardline. And that became a snag in the peace process.

But some of the community leaders also identified another problem: media misinformation. The town clerk lamented how the media hammed up fake news and unverified information. He even took time to set the record straight in the report by a newspaper that falsely claimed Igangan was so angry its youth attacked Gov. Makinde when he eventually visited. Akeem also worried why reporters made up body counts when there was none they verified.

It was a kind of irresponsibility.

And it distorted a lot of things, leading, sometimes, to despair or false hope—as in the narrative of perfect peace in Ibarapaland the state government and some Fulani leaders were pushing. This didn’t cut the exact figure. Nor did the post-Salihu calm many Igangan agitators and traditional leaders readily pointed at.

HRH Lasisi Adeoye commissioning Igangan police station in 2019

No doubt Adeyemo and his supporters notched up some victory on Jan. 26. But it cost both sides.

A day to the expiration of the ultimatum, emotions ran high in Igangan. Adeagbo described how fear gnawed at the heart of Asigangan himself. His subjects who no longer respected him were in war mode. His aged heart palpitated wildly. He had a gut feeling: death by a mob. Though it was a foreboding hunch then, his feeling was right. Bodies truly piled up when the dust settled in Igangan after the crisis.

Adeagbo said the jitters made Asigangan call Salihu hours before the action. “I am fleeing. I think you should, too, seriki.”

Fleeing was a huge toll the conflict took on Asigangan. He was over 80, weak-boned, slow, yet responsible for the safety of a wife, another younger woman, pregnant, and very young children in the palace. He, nonetheless, had to flee.

But seriki took the warning lightly.

“Are you just telling me now?”

The Fulani leader dug in his heels. He was ready to brace the odds.

Apart from his own domestic armed force, mostly his sons, Salihu, according to Adeagbo, had two state agents he paid to watch his back before Igangan youth and Adeyemo’s supporters advanced.

The two, Inspectors Erinfolami and Abioro, stood guard on the D-day, firing at the rampaging horde that over-ran Salihu’s estate.

Asigangan already fled. Eight of his subjects—youth—were shot and wounded by the cops, Adeagbo said. In the small war, three persons—all Fulani—were killed, their corpses deposited at Adaba Hospital’s morgue later. The Salihus eventually took off. Behind them was their gaa, in flames. He lost cars, N1.5 million, and 200 head of cattle. Adeagbo, however, doubted the clams.

The seriki Fulani of Oyo also lost his courage to return to Igangan. Even if he had it, his chances were slim. “We don’t want Salihu, Fulanis, and Bororos in Ibarapaland, especially Igangan,” Akeem declared. “United we stand on this.”

Salihu surely wouldn’t return.

But in Ibarapaland fear still shadowed many: Fulani, Yoruba, Abaku, and Bororo.

That, however, was not to say it was all gloom and doom down there.

Trending

Football1 week ago

Football1 week agoGuardiola advised to take further action against De Bruyne and Haaland after both players ‘abandoned’ crucial game

Health & Fitness2 days ago

Health & Fitness2 days agoMalaria Vaccines in Africa: Pastor Chris Oyakhilome and the BBC Attack

Featured6 days ago

Featured6 days agoPolice reportedly detain Yahaya Bello’s ADC, other security details

Comments and Issues1 week ago

Comments and Issues1 week agoNigeria’s Dropping Oil Production and the Return of Subsidy

Education7 days ago

Education7 days agoEducation Commissioner monitors ongoing 2024 JAMB UTME in Oyo

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoMaida, university dons hail Ibietan’s book on cyber politics

Crime7 days ago

Crime7 days agoPolice take over APC secretariat in Benue

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoDebt servicing gulps 56% of Nigeria’s tax revenue, says IMF

Pingback: IBARAPA: The Whirl before the Storm (2) | National Daily Newspaper

Pingback: IBARAPA: Killer of late Aborode arrested, remanded; suspect not Fulani | National Daily Newspaper