Featured

How Ogun-Osun River Basin fishery deepens flood misery in Isheri communities

Published

6 years agoon

By

Editor

As floods destroy homes and investments worth billions around the Isheri area of the border towns between Lagos and Ogun, the Ogun-Osun River Basin Development Authority is smiling to the bank, and everyone blames climate change.

The problem in the area is less about the rise in precipitation; it’s more of manipulation by the river basin authority who now turns the Oyan Dam reservoir into an aquabusiness, and releases water according to fish demand, at the expense of millions of humans living along the River Ogun in both states.

“The OORBDA has refused to release water in November to July as per the communiqué of May 2017 because it’s is operating the reservoir as a fish pond which generates huge profit to the organization,” the Isheri Community Association said in a report the National Daily obtained. The document was signed by Abayomi Akinde.

The November-July schedule is not an off-the-cuff arrangement. The communities, the Lagos and Ogun governments’ representatives, the OORBDA officials, and those of the Nigeria Hydrological Service deliberated on it for two days in May 2017.

It was then agreed, and documented, that the OORBDA should apply the best practice in the monitoring of the River Oyan Dam to stem the tide of flooding in the affected communities in Lagos.

Way back, especially in the 90s, Lagos was not this impacted by flooding. That was when the OORBDA was under the leadership of Tolu Fadahunsi, the son of the agency’s first director, the late S.O Fadahunsi. The communities remained flood-free up till the mid-2000s.

“The OORBDA used to release water from the Oyan Dam reservoir in November, December, January, February, March, April, May, June and July,” the community report stated. “And there was no water release during August, September and October.”

All of that has changed now. Commercial interest of the federal government agency overwhelms the well-being of the environment and the people.

The improper management of the Oyan reservoir now costs the two states a lot.

Since 2007, the communities along the river have been periodically submerged: in 2010, 2011 and now 2019. The flood levels in 2010 were 500mm (0.5m) higher than in 2007. The impact stretched as far as the Kara Market to the OPIC Estate to those areas around the Punch Place and others way beyond the flood plain—4 kilometers away from the river channel along the Lagos-Ibadan express.

The OORBDA is blaming climate change—the rise in sea levels and excessive precipitation. But it is not entirely easy to blame the elements for these ravages, which nobody can control, when measures for mitigation go unimplemented.

The amounts of rainfall so far now are not unprecedented, going by weather stats.

From NIMET records the community provided to prove their point against the OORBDA, the highest ever annual rainfall in south-western Nigeria has been 3784mm recorded in the Ikorodu area. The average annual rainfall in the catchment area of the dam is 1015.09mm.

Other indicators, like the maximum annual rainfall between 1991 and 2001 was 1911mm at Itoikin, Lagos; maximum annual rainfall in the period 1990 to 2010 was 1471.8mm in Shaki in 1995; 1596.4mm in Iseyin in 1991; 2321.1mm in Lagos Marina in 2004; and 1615.7mm in Abeokuta in 2007 respectively.

According to the community, it would serve the public interest if NIMET provides its rainfall figures at these locations for 2018 and 2019 because the data OORBDA provides is arguable.

“Rainfall data is usually given in millimeters but OORBDA has specified rainfall in the period May 2019 to October 2019 in centimeters, giving a total rainfall for the period as 770.05 centimeters or 7,700.5 millimeters,” the report stated.

“It would appear that this rainfall data is meant to confuse the public as this level of rainfall could only arise from extreme weather events which are not prevalent in Nigeria.”

The second reason the agency serves up is that the communities settled on the Lagos flood plains around the River Ogun, and so would essentially suffer flooding when the river brims over.

Plain flooding is observed over a century, during which rainfall will vary in volumes from year to year so that there will be a period or two of maximum rainfall in those areas around the river.

So for the Oyan River, flooding is expected to occur at an interval of 10 years to 25 years in the flood plain. That’s only on one condition: if there are no dams built on the river to control the water levels. But there are—two of them: the Oyan Dam in Abeokuta South and the Ikere Dam built on the River Ogun at Ikere, Oyo state.

“How does one explain then—that with the construction of the two dams, people in the area are worse off as floods now occur every year?”

Had the OORBDA not gone for broke on fishery, the roles of the two dams would have helped reduce the impact of climate on these areas.

The Oyan dam, with its 270-million-cubic-metre reservoir capacity, was designed also for power generation. Three turbines with 3MW generating capacity each were commissioned along with the dam by the late President Shehu Shagari.

If the turbines were in use, they would require about 2 million cubic meters of water each day to drive them. That would be about 720 million cubic metres yearly. The dam’s total average run-off from the catchment area of the reservoir is about 822.2 million cubic metres per year.

With such reservoir space, the dam will be empty if there is no water coming into the reservoir in about 130 days. And if the water release is properly regulated as agreed in the 2017 summit, there would be just about 100 million cubic metres to contain yearly —less than the reservoir full capacity.

Operating as a fish pond now, the Oyan dam reservoir lets out flood of water at the most inappropriate time.

And when the huge volumes of water are released, a lake is formed on the river between Magbon and Ilate, two of the many tributaries along the Ogun River system.

A second channel, the Isheri community explained, takes off from this lake to the east of the main channel of the River Ogun. This second channel carries water directly to the concrete viaduct (long bridge) on the Lagos-Ibadan expressway at latitude 60 40’ 00”N, then onwards into River Owuru which flows into Majidun Creeks, discharging the water into the Lagos Lagoon.

The flood paths from the main channel of the River Ogun and the lake cover Ogun and Lagos. So does the impact: a disaster area which stretches 27 kilometres long, and 4 kilometres wide. There are schools, estates, factories, offices, and residential properties in the middle of this disaster.

For all these, blame the climate, the OORBDA would say. Even when there’s no data to back this.

The climate is changing, no doubt. But current rainfall levels are not as high as in the past. “It is these past 100-year records that are used in dam design,” the Isheri document added.

It also dismisses the suggestion that the rise in Atlantic Ocean is forcing Lagos Lagoon water level to rise. “If, in fact, there is a noticeable rise, the first place that would be affected are Apapa Wharf and the Governor’s House on the Marina, Lagos.”

Based on projection during the second half of the 20th century, global sea levels rose by 1.8mm each year with 1.1mm of the rise coming from melting ice canopy and glaciers. Since 2000, global sea levels rose by 32.4mm, and the Apapa Wharf, Marina in Lagos Island, and others have not been affected by the sea-level rise.

So the river basin authority will need more than blanket statements to refute the communities’ allegation—that turning the dam to a fish farm is jeopardizing lives and environment.

Trending

Health1 week ago

Health1 week agoExpert warns smokers, people with high cholesterol face elevated diabetes risk

Latest7 days ago

Latest7 days agoTwo more Rivers lawmakers call for halt to Fubara impeachment

News1 week ago

News1 week agoJakande Estate residents allege illegal demolition, tasks Sanwo-Olu

Business6 days ago

Business6 days agoRising fuel costs, policy push signal EV boom in Nigeria as industry predicts 2026 takeoff

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoFG, KPMG meet in Abuja to resolve disputes over new tax laws

Business7 days ago

Business7 days agoNCC engages PwC to conduct comprehensive competition review of Nigeria’s telecoms sector

Latest1 week ago

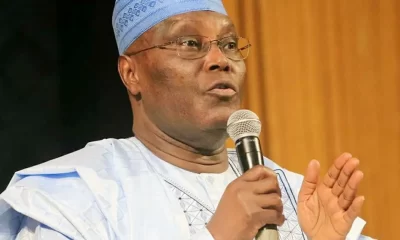

Latest1 week agoAtiku slams arrest of Ambrose Alli University students, accuses Tinubu administration of intolerance

Latest7 days ago

Latest7 days agoKwankwaso tells NNPP members to discreetly sign defection forms amid Kano APC shift