Comments and Issues

Looming dangers to Nigeria’s N28.7 Trillion Budget

Published

4 months agoon

By

Marcel Okeke

The news is shocking, to say the least, that “no fewer than 157 incidents of crude oil theft were recorded in the Niger Delta between December 30, 2023 and January 5, 2024.” A space of one week! The Nigerian National Petroleum Company Limited (NNPCL) said the cases were recorded from several incidence sources. They include: Nigeria Agip Oil, 62; Pipeline Infrastructure Nigeria Limited, 29; Maton Engineering Limited, 18; Tantita Security Services Limited, 8; NNPCL Command and Control Centre, 2; Shell Petroleum Development Company, 4; and government security agencies, 34.

Also, according to a short video posted on its X handle on Tuesday, January 9, 2024, the NNPCL disclosed that 52 illegal refineries were discovered and destroyed in Abia, Imo, Rivers, and Bayelsa States. Similarly, the NNPCL revealed through the video that buried drums of crude oil were unearthed and some were discovered in bushes. It is also reported that in Oporoma, Bayelsa State and Oleh in Warri, sacks of stolen crude oil were discovered and confiscated; and in Delta State, drums filled with stolen crude oil were found in the river, while oil well heads were vandalized in Rivers State.

The disheartening report also showed that within the past one week, 25 cases of pipeline vandalism were recorded across several communities. “12 vehicles conveying stolen crude were arrested in the past week across several locations in Rivers and Delta States, while 24 wooden boats conveying stolen crude were arrested and confiscated.

“Nine of these incidences took place in the deep blue water, 45 in the Eastern region, 95 in the Central region, while eight took place in the Western region,” the NNPCL report said. As these criminalities were being perpetrated, there is also a noticeable decline in oil rigs in the Niger Delta, a situation that constitutes a threat to the government’s projection to raise crude oil production to 1.78 million barrels per day (bpd) this year. Data obtained from Baker Hughes Incorporated and the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) show that all through 2023, Nigeria’s rig count, which indicates the level of oil production activities by operators, averaged 14, a sharp decline from about 35 in 2018.

As a mono-product economy, Nigeria’s oil sector still provides for upwards of 90 per cent of its foreign exchange earnings and about 70 per cent of its entire budgetary revenue. In the 2024 budget with an aggregate revenue of N18.32 trillion, oil shall account for about N8 trillion—leaving the rest to non-oil and independent and other sources. Therefore, the significant drop in rig count (from 45 to 14) and widespread stealing of crude oil largely imperil the budget and its revenue projections.

An oil industry veteran, Austin Avuru, who is the executive chairman of AA Holdings, says Nigeria’s oil industry is facing a stark reality check as it needs 45 new rigs to reach “normal” production levels of 2.1 million barrels per day (bpd). “To arrest the natural decline and add 800,000 barrels per day over two years will require 426 wells including 106 exploration and appraisal wells as well as 320 development wells,” Africa Oil & Gas Report, an energy intelligence publication, quoted Avuru as saying. “For this, 45 rigs must be on duty; so the country needs an investment of US$7.6 billion in oil well costs alone.”

Available facts and figures show that between 2009 and 2020, 619.7 million barrels of crude oil, valued at US$46.16 billion (N16.25 trillion) were stolen. From 2017-2021, 208.639 million barrels of crude oil and petroleum products, valued at US$12.74 million (N4.325 trillion) also got stolen. In recent years, the thieves have been getting more desperate and sophisticated, leading to an average daily loss of between 437,000 and 200,000 barrels per day.

The dangers of rising spate of crude oil theft in Nigeria are far-reaching and multifaceted, impacting the environment, economy, and social fabric of the country. One of the core dangers is environmental (pollution): crude oil spills caused by pipeline tampering contaminate water and land, poisoning drinking water and devastating ecosystems. This harms both aquatic and terrestrial life, threatening food security and livelihoods. Oil thieves often clear forests to access pipelines, contributing to deforestation and the loss of biodiversity. This exacerbates soil erosion and disrupts the delicate balance of the ecosystem. Spills and leaks contaminate the soil, rendering it less fertile for agriculture and causing long-term damage to the land’s productivity.

Without a doubt, oil theft deprives the government of precious revenue that could be used for funding vital public services like healthcare, education, and infrastructure. This hinders development and fuels poverty—a clear picture of what Nigeria is already experiencing. The instability and risks associated with oil theft make the sector less attractive to investors, limiting foreign direct investment (FDI) and stifling economic growth. Major oil companies are rather quitting the country.

On the social front, oil theft and its associated activities, like bunkering and smuggling, often lead to violent conflicts between rival groups and with security forces. This creates an atmosphere of fear and insecurity, hindering development and social cohesion. Also, the lucrative nature of oil theft attracts corrupt elements, fostering a culture of impunity and undermining the rule of law. This further weakens governance and perpetuates the cycle of crime as is already the case in most parts of the Niger Delta.

As these unscrupulous elements are undermining the national interest through their criminal activities, the oil sector is yet being buffeted by numerous other challenges (including external and internal headwinds). This assertion chimes in with Jim Orife, former general manager of Nigerian National Petroleum Company (NNPC) Ltd, who said there was little or no strategy for implementing any energy plan policymakers had drawn up for the country in the last 10 years.“We have remained on the same spot. We are not unlocking anything,” Orife, a foundation staff member of NNPC in 1977, said at the recent National Association of Petroleum Explorationists (NAPE) conference in Abuja.

Another challenge facing the oil industry is the sale of assets by most International Oil Companies (IOCs); otherwise called ‘oil majors’ such as Shell, ExxonMobil, Eni and TotalEnergies. Today, oil fields that once accounted for more than two-thirds of all Nigerian oil production no longer represent value for the IOCs, whose access to financing is critical for their development. “Divestments by oil majors used to provide local operators an opportunity to prove their mettle, taking declining fields past production peaks, and improving host community relations to deliver higher royalties to the government; now local operators are scrambling to extract value from divested fields,” an energy lawyer at a Lagos-based oil firm said.

There is already palpable fear that this spate of divestments in an oil industry troubled by existential threats without new investments could herald Nigeria’s decline as a major oil producer. Already, one or two African member countries of OPEC have overtaken the country as the largest producer/exporter of oil. It is being widely alleged that despite the introduction of the Petroleum Industry Act (PIA), regulatory agencies still demand for bribes or incentives to attend to licences and approvals of oil rigs, and the delay in the process and bureaucratic obstacles have not changed.

The existing business operating models in the country have not also helped in developing the hydrocarbon industry in Nigeria. The NNPC uses joint venture agreements with local and international oil companies (IOCs) to produce onshore and shallow-water oil wells. It owns 60 percent of benefits in these agreements but often fails to contribute its share of costs, leading to what is known as ‘cash call arrears’ in the industry. This development means rig maintenance is often neglected, leading to equipment failures and avoidable environmental pollution/spills.

These factors and the continued exodus of the IOCs really constitute a worrisome threat to not only the revenue projections in the 2024 budget but also to the viability of the oil industry in Nigeria. A few weeks ago, the Norwegian oil corporation Equinor ended its three-decade partnership with Africa’s biggest oil producer, announcing that it had sold its Nigerian subsidiary to a little-known local business called Chappal Energies. Earlier on last year, Italy’s Eni declared that it would sell its onshore division to the local business Oando. Before this, China’s Addax sold its four oil blocs to the Nigerian National Petroleum Company.

The US behemoth ExxonMobil had also planned to sell its four onshore oilfields for approximately US$1.3 billion to Seplat, an energy business with dual listing in London and Lagos. However, a few days after giving an approval to the contract in August 2022, former president and oil minister, Muhammadu Buhari, reversed the deal. The transaction is yet pending. Similar circumstances have befallen Britain’s Shell, which has indicated that it would like to withdraw from onshore fields that might bring in up to US$3 billion but is still mired in legal disputes that are impeding its progress.

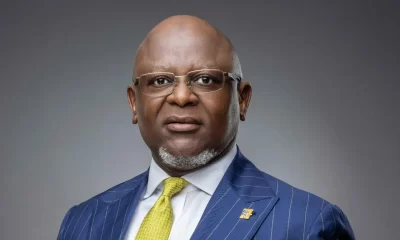

- The author, Okeke, a practising Economist, Business Strategist, Sustainability expert and ex-Chief Economist of Zenith Bank Plc, lives in Lekki, Lagos. He can be reached via: [email protected]

Trending

Health & Fitness3 days ago

Health & Fitness3 days agoMalaria Vaccines in Africa: Pastor Chris Oyakhilome and the BBC Attack

Featured1 week ago

Featured1 week agoPolice reportedly detain Yahaya Bello’s ADC, other security details

Aviation5 days ago

Aviation5 days agoWhy some airlines are avoiding Nigeria’s airspace–NAMA

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoDebt servicing gulps 56% of Nigeria’s tax revenue, says IMF

Aviation4 days ago

Aviation4 days agoJust in: Dana airline crash lands in Lagos

Aviation4 days ago

Aviation4 days agoNSIB begins investigation into Dana Air after crash-landing incident

News7 days ago

News7 days agoOndo APC guber hopefuls reject primary poll

Business1 week ago

Business1 week agoAdesola Adeduntan steps down as FirstBank CEO