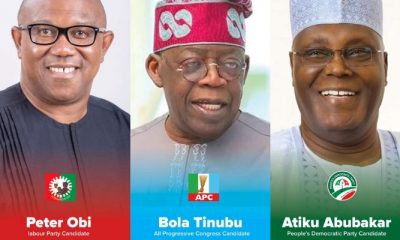

Sowore’s critique of Labour Party’s Peter Obi and Yusuf Datti Baba-Ahmed a few days ago after the duo visited former military Heads of State, General Abdulsalami Abubakar and General Ibrahim Babangida, in Minna, is a spark of this idealistic fire that has set him apart. He’s been consistent in refusing to dine with those he once raised placards to challenge at protest grounds from Lagos, down through New York City, to Abuja, and this inspired his rush to demonise his opponents’ political pilgrimage, calling them “apprentices, accomplices, minions, and cronies” of the past leaders who, he wrote on his Facebook, had “robbed Nigeria blind, murdered its citizen, and sabotaged its aspirations for greatness”.

Sowore is as polarising in politics as he was as a combative media practitioner, and, interestingly, his transition to partake in the game of begging for votes has not tamed his antagonism towards the government and the political establishment. It has only brought him back to the country he aspires to rescue, and closer to the vengeance of the hostile characters he had characterised and mischaracterised on his platform as a newsman. His confrontational politics also shows he’s not even practising to be the version of politicians that excel in Nigeria. He’s still trapped in his activist fatigues.

Even though I’ve caricatured some of his paranoid political views and he knew it, especially the anarchic tendencies of some of his positions like exploitable Revolution Now protests and his uncritical defence of Nnamdi Kanu, I always applaud his sense of independence. He’s also tolerated my disagreements with his methods and the think-pieces written to oppose some of the sensationalising reports dispensed by the media and campaigns he led, which, I feared, colour the width of ethno-regional and religious fault-lines in the country.

As an angry millennial in search of a platform to share my perspectives of Nigeria’s political misadventures, Sahara Reporters was a willing sanctuary, and so my generation of political observers and analysts owe Sowore a debt of gratitude for the opportunities to get our voices heard. He founded a platform that told truth to power, and, even with its flaws, you can’t tell the history of Nigeria’s First Republic without its “nuisance value”.

This essence of Sowore was the reason I emailed to meet him when I found myself in New York City a few years ago, and staying at Millennium Broadway Hotel, which is in Midtown Manhattan, the same borough as the famous Sahara Reporters Headquarters. “Will be most happy to finally meet you in person. I love your writing and follow you all the time (as you know),” he wrote in honouring my request to meet. He was running the New York Marathon that week, so we couldn’t meet immediately.

When we finally arranged to meet, it turned out that our stations were just seven minutes apart. Approaching the address, I remember being amused and telling myself that if Nigerian politicians had the power to nuke Sowore, an engine room of their misfortune, they would have done so. Unfortunately, I needed a key card to gain access to the building, and my phone was down. That’s how I missed the chance to pay my respect to this fearless Nigerian.

We got to meet in Abuja, and, ahead of the 2019 presidential election, I also volunteered to defend him against those who kicked against his bid even though he wasn’t my favourite option in the election I wasn’t even in the country to vote. Sowore’s worst disadvantage has been, strangely, what ought to make him the favourite of the people—his idealism. He’s refused to be the kind of politician who excels in our clime, the ones that form alliances with even their worst enemies and critics to reach their political height.

This idealistic proclivity must’ve sabotaged his politics, but it’s laudable. For so long our politics was defined as a no-go area for citizens unwilling to roll in the mud or kowtow to self-appointed kingmakers ruling from palaces that should never have existed, from Minna to Ota. While firebrands like Aminu Kano were given a chance to at least think for a government they failed in their bid to lead, others like Gani Fawehinmi were betrayed by the very masses they spent their lives fighting for, ending up in jails in their pursuits of justice.

So, Sowore’s refusal to acknowledge politics as a morally-conflicting enterprise is good for the people. He aspires to be the opposite of those who visit the hilltop residences of our political influencers and kingmakers to kiss the ring, and, while history may favour him and remember him fondly, his proximity to the seat of power widens each time he roars against those his supporters perceive as the devils.

A segment of Peter Obi’s supporters rooted for Sowore in his 2019 presidential bid, and they’ve registered their objections to Obi’s visits to the former presidents they vilify fiercely, aligning with Sowore’s thoughts. But the difference between Sowore and Obi is that the latter is a thoroughbred politician. As a former governor, one who has won elections and fought hard to protect his mandates, he knows the system too well to realise that mere endorsement by the people isn’t enough.

There’s a victory that may await Sowore, though. His politics may be valorised as a breakthrough of a candidate independent of the establishment if he escapes career-wrecking scandals in doing so. This could be his victory against the elite whose consensuses have long been our only solutions. We must make our politics practicable for all. Sowore should be scrutinised and judged fairly, a tradition with which he’s of course familiar. But laughing at his bid is finding our misery funny.