Crime

Man-snatching: The underworld market risk-preneurs feign to hate

Published

8 years agoon

By

Olu Emmanuel

Fear, figures, and fact-bending make kidnapping seem Nigeria’s biggest palaver. Not by a long shot, though, especially for poor dads, mums, and those between.

By SEGUN ELIJAH

ROUND the world, in the last five years, roughly 60,000 people have been kidnapped. That’s about twice the population of Monaco, a country in Western Europe. No fewer than 2,184 of the kidnap victims were Nigerians—or kidnapped in Nigeria—between 2009 and 2012, according to police reports.

And further data mining reveals for 12 years, kidnapping took a quantum leap among crime stats in the world’s most populous black nation. From 24 cases in 1999 to 512 in 2008, kidnap figures ramped up to 703 by 2009, peaking at 738 in 2010, at the height of the Niger Delta resource struggle, as the UN Office on Drugs and Crime 2013 survey on global crime put it. That was the same year CLEEN Foundation, an NGO focusing on crime and security statistics, claimed 5 per cent of the 11,518 citizens it surveyed had been kidnapped.

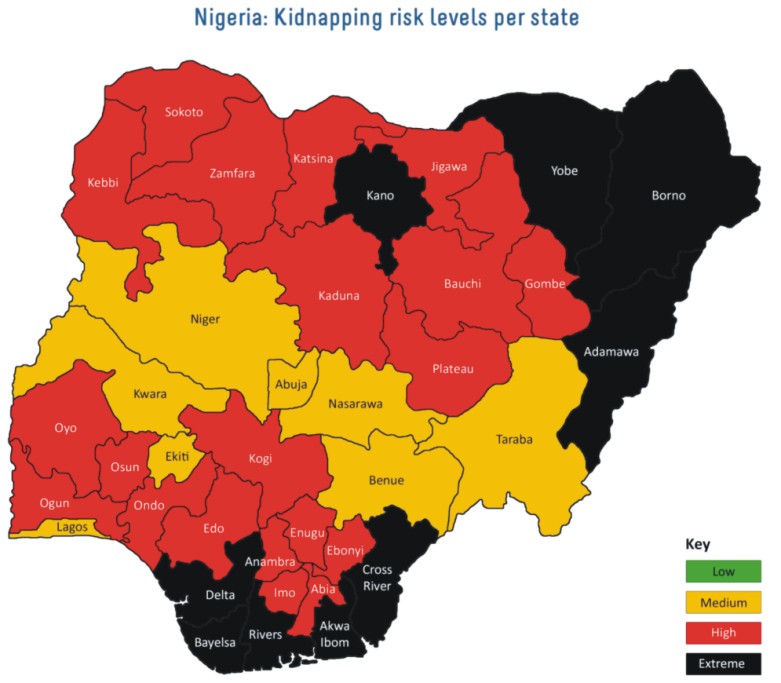

The survey also nailed the southwest as Nigeria’s kidnap hotbed. That’s contestable now. Crisis management firm Red24 said Lagos, going by the rate of the incidents in 2015, hit medium on the threat level, compared to other south-western states marked high, and the south-south checked off as extreme. Unfortunately, the Babington Macauley schoolgirls kidnap, the fourth incident in Lagos in 2016, has bumped up the risk dial in the state.

But all this data-splitting about kidnapping in Nigeria isn’t just for public service, looking at how the figures are usually ballooned. “From investigations conducted thus far, it is clear that the problem is considerably exaggerated,” said Lagos ex-Justice Commissioner Ade Ipaye in 2013, when a local government chairman was kidnapped. He struck a chord saying that. Kidnappings clearly pinned on terrorists, anarchists, spiritualists, and bitter rivals usually get mashed with the enterprise ones. And the figures, thoroughly chewed in the mouths of motivated risk analysts, can give Nigerians the creeps. And that’s just the ticket–for the ventures to squeeze out more grant dough or contract payouts. Among those you can damn for hamming it up are K&R insurance experts and sociopreneurs doing a roaring trade of fearmongering.

The K&R policy alone has been garnering $250 million annually across the world. You can pinch some Western gangbusters, too. The CIA and the US Department of State’s Overseas Security Advisory Council (OSAC) spin rolls of blood-and-thunder intel on Nigeria every year–in the name of protecting Americans doing business in Nigeria. Yet 84 per cent of those kidnapped for ransom, the NYA reported, were Nigerians.

There’s still a lot more on the credit side: Since 2010 when the crime hit the roof, the numbers of incident have been retracing by leaps and bounds. By the time CLEEN raised hell about kidnapping three years ago, 574 incidents were recorded—down from 938 three years before. So the figure has been plummeting. There were 48 in 2014, and 21 last year, compared to the yearly 300,000 K&R incidents Red24 claims take place globally. And so far now, in spite of the ‘extreme’ tag NYA and other risk mappers gave Nigeria in the 2016 outlook, only 23 incidents of K&R have been recorded. Kaduna and Rivers lead with five and four respectively, while Lagos has three.

Even on the global scale, the kidnap figures show Africa is on the mend: 37 per cent of the world total in 2013 down to 30 per cent in 2014.

That more Nigerians are now targeted by the kidnappers makes a slender hope of the falling kidnap stats. But not to worry. In the Kidnap and Ransom industry, the baddies aren’t looking for their catch among the over 100 million bean eaters that rub along on $2 daily in Nigeria. The “manjackers” prey on fat cats—like they did in the over 21 incidents recorded last year. Freedom House, a pro-democracy and freedom NGO, even said in its 2014 report the main targets for kidnapping are political figures, the wealthy, and foreigners. Other risk mappers confirm this, too. “Abductions continued to be predominantly politically-motivated, targeting high-profile domestic nationals,” NYA stated in its 2016 Risk Map. With the widening middle class in Nigeria, however, those ne’er-do-wells might have hit pay dirt nabbing the well-heeled presenting like fair game.

Every year, $1.5 billion slushes around the K&R industry world-wide, according to the Global Black Market Information. And the underworld players that make the industry tick in Nigeria have their slice of the dirty money. Between 2006 and 2010, Nigerian kidnappers, police said, got $100 million in total ransom. On the average, they demand $2 million for a professionally executed kidnap. There are other hit-or-miss operations that fetch lower than that. Express kidnapping, according to OSIAC, is a quickie that fetches fast but few bucks. (Mexico alone records 6,000 every year.) Bastards in rich families across the nation have also been organising abductions to extract extra money.

While the K&R market dwindles in Nigeria, the scramble for big stakes increases. Next up to join security advisers, insurance policy sellers, NGOs, risk mappers, bad cops, and kidnappers in pushing the K&R business is another class of professionals: negotiators.

Nigeria hasn’t got one yet. And business-smart negotiators from London have been doing brisk business negotiating ransom here. Terra Firma, for instance, has haggled down cash prices in a raft of negotiations to save foreigners snatched in Nigeria. Many of their clients are oil and construction giants that can afford flying in the negotiators.

But for Nigerians who suffer the most, there’s no local professional K&R negotiator to price down the ante. The victims’ families, out of fear, then have to pay more. The relatives of Olu Falae stumped up N2 million when the ex-finance minister was abducted last year. In 2014, then Rivers transport commissioner also paid N5 million to secure the release of his mother abducted.

Many hostages have paid so dearly to save their lives. The police don’t like this, however. And they will do everything to deny offering loads of cash to ease rescue operations on occasions. “Our strategic response has always been to discourage payment of ransom,” IGP Solomon Arase said while declaring open a counter-kidnapping training in Abuja February 2. “But we are also worried about the safety of the victims.” The worry probably accounts for the reason the K&R niche remains attractive.

Experts believe paying ransom is a problem. It bolsters kidnappers to enter and stay in business, knowing their victims can plunk down whatever the ransom is. The Nigeria police are yet to get a handle on kidnapping either, especially in the use of cutting-edge gizmos. According to Don Okereke, an industrial security expert, the police can’t track kidnappers’ calls real-time for now.

So there’s little the security agencies can do to stop anxious victims from pumping money to their kidnappers. And, somehow, it’s cool, too, for all the legit businesses and advocacy ventures (anti-capital punishment activists) springing out of the K&R niche. They will have lots of data to crunch, thickening the anxiety enough for patrons and donors to yield their purses. The entire kidnap value chain will then be able to stay afloat.

You may like

Osun govt addresses possibility of lifting curfew on Ifon, Ilobu communities

Lagos, Ogun police begin joint patrols on Lagos-Ibadan expressway

How I discouraged ransom payment until I was kidnapped — Former DSS Director

Bandits reportedly abduct at least 50 wedding guests in Katsina State

Over 1,000 SGBV cases recorded in Kaduna

Man brutalizes his wife for putting marks on their children

Trending

Football5 days ago

Football5 days agoGuardiola advised to take further action against De Bruyne and Haaland after both players ‘abandoned’ crucial game

Aviation7 days ago

Aviation7 days agoNCAA suspends three private jet operators for engaging in commercial flights

Aviation6 days ago

Aviation6 days agoDubai international airport cancels flights as flood ravages runway, UAE

Featured3 days ago

Featured3 days agoPolice reportedly detain Yahaya Bello’s ADC, other security details

Comments and Issues5 days ago

Comments and Issues5 days agoNigeria’s Dropping Oil Production and the Return of Subsidy

Education4 days ago

Education4 days agoEducation Commissioner monitors ongoing 2024 JAMB UTME in Oyo

Business4 days ago

Business4 days agoMaida, university dons hail Ibietan’s book on cyber politics

Featured1 week ago

Featured1 week agoRelationship between Oyetola, Omisore remains cordial — Osun APC